The fact we’re up to “Part 8” illustrates there’s a lot to talk about once you take performance analysis down to the individual logical / physical processor level.

Many people have talked about the need to avoid LPARs crossing processor drawer boundaries. There are good reasons for this – because access to cache or memory in another drawer incurs many penalty cycles – where the core can’t do anything else.1

This post is about verification: Checking whether cross-drawer access is happening.

How Might Cross-Drawer Access Happen?

There are two main reasons why cross-drawer access might happen:

-

If an LPAR has too many logical cores – say, more than a drawer’s worth – they will be split across two or more drawers.2 When I say this, I’m talking about home addresses, rather than guaranteed dispatch points.

-

Vertical Low (VL) logical cores – those with zero vertical weight – can be dispatched on any physical core of the corresponding type, including in a different drawer. The trick is to avoid dispatching on VL’s as much as possible.

One mitigating factor is that most work in a z/OS system is restricted to run on a small subset of cores – its Home Affinity Node. These are generally in the same chip so sharing certain levels of cache.

How Might You Detect Cross-Drawer Access?

John Burg has for many years proposed a set of metrics. I will introduce the relevant ones in a minute.

Cache Hierarchy

To understand the metrics you need at least a working knowledge of the cache structure of the processor.

On recent machines it logically goes like this:

- Every core has its own Level 1 cache

- Every core has its own Level 2 cache

- Cores share a Level 3 cache

- Cores share a Level 4 cache

I’ve left the descriptions a little vague – deliberately: It can vary from generation to generation. Indeed z16’s implementation is very different from that of z14 and z15.

The deeper into the cache structure you go to obtain data the costlier it is in terms of cycles. And memory accesses are costlier even than Level 4 cache.

It is only at the Level 4 cache and memory levels that it’s possible to access remotely – that is data in another drawer.

SMF 113

Long ago – on z10 – SMF 113 was introduced. It documents, among many other things, data accesses by the z/OS system that cuts the record. It does not know about other LPARs.

SMF 113 contains a number of counter sets. Two of these counter sets are relevant here:

- Basic Counter Set

- Extended Counter Sets

Basic counters are present on all generations of machines since z10. Such counters follow the naming convention “Bx”. For example, B2.

Extended counters vary from generation to generation. Indeed they follow the cache hierarchy model of the machine generation. As previously mentioned, z14 and z15’s design differs from z16’s. So the extended counters for z14 and z15 differ from those of z16. Indeed counter numbers (“Ex) are sometimes reused. An example of an extended counter is E146.

Using The Counters

Let’s look at the relevant metrics John defines.

- Level 1 Miss Percentage (“L1MP”) is percentage of accesses that aren’t resolved in the L1 cache.

- Level 2 Percentage (“L2P”) is the percentage of L1 cache misses resolved in the L2 cache.

- Level 3 Percentage (“L3P”) is the percentage of L1 cache misses resolved in the L3 cache.

- Level 4 Local Percentage (“L4LP”) is the percentage of L1 cache misses resolved in the L4 cache in the same drawer.

- Level 4 Remote Percentage (“L4RP”) is the percentage of L1 cache misses resolved in the L4 cache in a different drawer.

- Memory Percentage (“MEMP”) is the percentage of L1 cache misses resolved in memory in the same or a different drawer.

These metrics are all composed of multiple counters. So I can split MEMP into two, with a slight renaming:

- Memory Remote Percentage (“MEMLP”) is the percentage of L1 cache misses resolved in memory in the same drawer.

- Memory Remote Percentage (“MEMRP”) is the percentage of L1 cache misses resolved in memory in a different drawer.

Obviously MEMP = MEMLP + MEMRP.

L4LP and MEMLP combine to form local accesses where there was the hierarchical possibility of remote accesses. Similarly L4LP and MEMRP combine to form remote accesses.

I don’t think I would necessarily compute a ratio of remote versus local but the following graphs are nice – particularly as they show when remote accesses are prevalent.

It should also be said that L2P, L3P, L4LP, L4RP, MEMP, MEMLP, and MEMRP are all percentages of something quite small – L1MP. Generally L1MP is only a few percent – but we care about it because L1 cache misses are expensive.

Here is a view of all the Level 1 Cache Misses. The total wobbles around 100% a bit. I’ve found this to be typical.

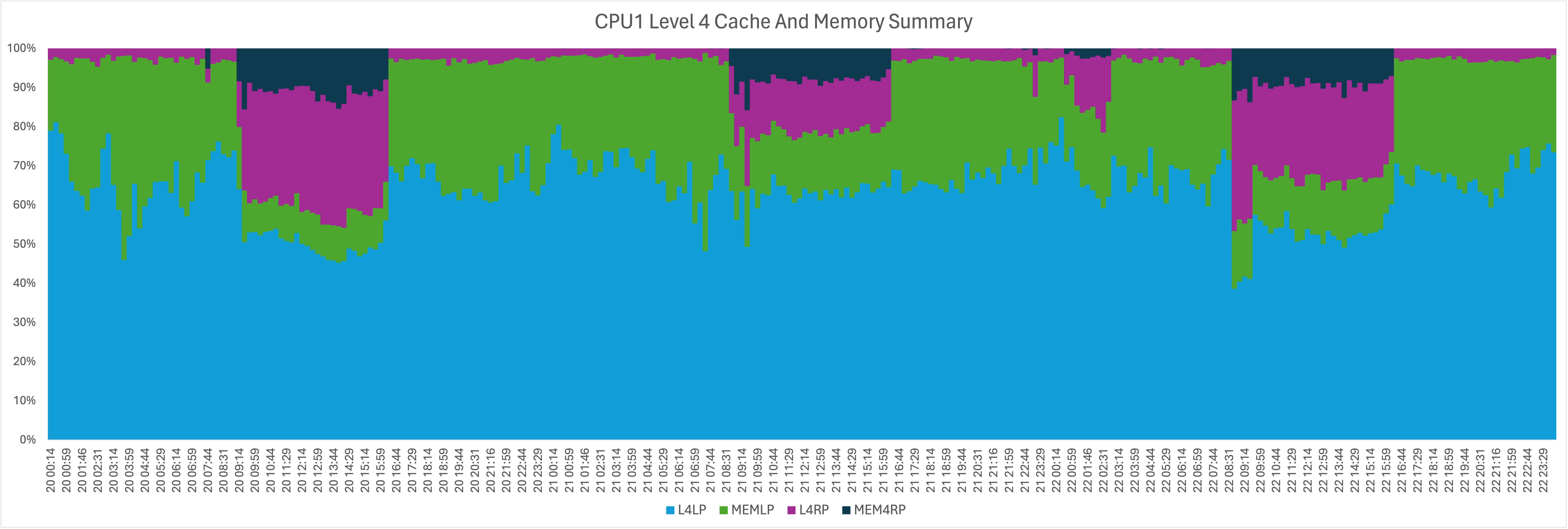

And here is zooming in on the only components where there is potential for cross drawer.

You’ll see from both of these there’s a “time of day” thing going on.

Conclusions

Some LPAR design commonsense is worthwhile:

- Minimise the risk of LPARs having theire home addresses being split across drawers.

- Minimise running on vertical lows. (Yes, some might be inevitable.)

The point of this post is to show you can measure cross-drawer access. It’s worth keeping an eye on it, especially if your LPAR design leaves you prone to it.

While the higher the cost the further you go into the cache hierarchy, it would be extreme to have a design criterion that LPARs fit into a single DCM, let alone the same chip; Many customers would find such a constraint difficult. Indeed cross-LPAR communication might well negate the benefits.

Finally, a processor in “the main drawer” could be accessing cache or memory in a remote drawer. Equally, it could be a processor in “the remote drawer”. Not that there is a real concept of “main drawer” or “remote drawer”; It’s a matter of statistics. So “local” and “remote” are relative terms. But they are useful to describe the dynamics.

Making Of

I started writing this on my first attempt to fly to Copenhagen today. The plane was broken but there was a lot of time stuck on the plane before we decamped. A couple of hours later I more or less finished it on the second plane – which did take off.

Then, of course, I fiddled with it… 😃

Who says travel is glamorous? 😃 But, as I like to say, today’s travel bother is tomorrow’s war story…

… And I am finishing this off in my hotel room in Copenhagen after my second trip – to GSE Nordic Region conference. That was a very nice conference.

2 thoughts on “Engineering – Part 8 – Remote Access Detection”