(Originally posted 2011-10-17.)

I’ve been looking for an excuse to reference the excellent B52’s Channel Z ever since we started talking about "z". And this is, I think, a good one. 🙂

(Notice BTW the URL in the previous paragraph makes it clear SING365.com (should be "SING360" 🙂 ) is using Domino.)

So, back to the matter at hand…

A customer I’m working with is using Intelligent Resource Director (IRD) Weight Management together with HiperDispatch. Note: I said "Weight" not "Logical Processor" because you can’t use IRD Logical Processor Management with HiperDispatch. The way this works is that IRD changes the weights – if it needs to – and HiperDispatch recomputes the vertical weights and (potentially) adjusts the number of Vertical High, Vertical Medium and Vertical Low processors accordingly. (Adjusting these counts is not the same as parking and unparking, which is an important point to bear in mind.)

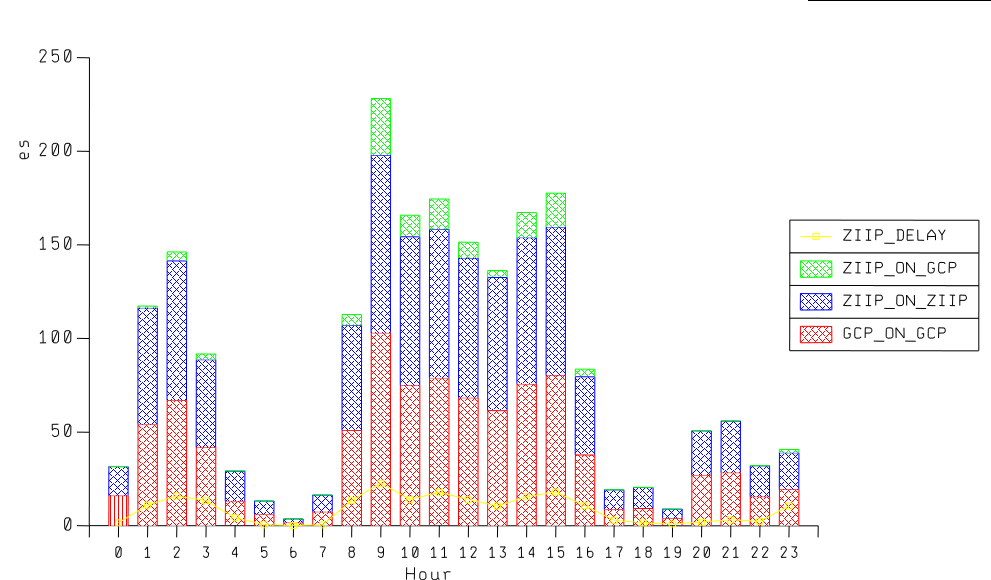

My personal interest is as much about how to tell the story as it is about the actual performance. Well, not quite. So, in this case the story is that weights shift within an LPAR Cluster between one LPAR and another. This happens, in my analysis, in a credible and smooth way. There’s no "nervous kitten" here. So the HiperDispatch adjustments happen as well. But how do we show this?

Showing the shifting weights is easy: Stack up the weights for the LPARs by time of day. The total stack height remains constant – which we should expect. (IRD only shifts weights within the cluster.)

The complicated thing to depict is the number of High, Medium and Low logical processors. The easy bit is to do this by time of day. But suppose, as I was, you’re producing an LPAR layout table? Which is a static depiction. Well, let’s rehearse what the instrumentation available to us is…

APAR OA21140 does a number of things. The relevant thing it does is to introduce SMF70POF in the SMF 70 Subtype 1 record. It’s in the Logical Processor Data Section, and you get one for each logical processor in each LPAR. The field tells you whether the logical engine is vertically polarised and whether it’s High, Medium or Low. (As the Low ones can get parked it helps explain the parking and unparking elements of HiperDispatch’s behaviour.) I take this to be the state at the end of the RMF interval and note there’s a bit which says if it changed during the interval.

This is easy to use in a table if you have a static situation. But, of course, IRD Weight Management makes it dynamic. So, when I summarise over a shift (of maybe 8 hours) some logical engines have changed between Medium and Low (and maybe some are only sometimes High). It all depends on the degree of shifting of weights. So some logical engines aren’t totally in one state throughout the 8-hour shift.

Here’s a way around the problem:

I define a fourth state in my reporting: "Vertical Transitioning" . So you might see an LPAR in my table as, for example, "VH:2 VM: 1 V?: 1 VL: 8". In this example 2 logical engines remain Vertical Highs all the time, 1 is always a Vertical Medium, 8 are always Vertical Low engines. Finally the "V?" means one logical engine transitions between states (possibly VM and VL).

"Vertical Transitioning" isn’t a technically recognised term but I think it captures the essence of the behaviour. Of course there’s wouldn’t be any Vertical Transitioning engines if IRD weren’t shifting the weights.

Which brings me back to the B52’s: "Channel Z’s All Static All Day Forever" is anything but true these days. 🙂

without necessarily giving it too much thought. But what is this "splodgeness" whereof we speak?

without necessarily giving it too much thought. But what is this "splodgeness" whereof we speak?