I call this “Part 0” because I haven’t yet seen any data. However I think it useful to start here, rather than waiting for customer data to appear – for two reasons:

- Sharing what data is available is useful.

- Showing how “folklore” is built is instructive and useful.

As you might expect, I’ve been down this way many times before.

What Sustainability Metrics Are

With z17 some new instrumentation became available. It appears in SMF 70 Type 1 records – in the CPU Control Section. Here are the fields:

| Offsets | Name | Len | Format | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 432 1B0 | SMF70_CPUPower | 8 | binary | Accumulated microwatts readings taken for all CPUs of the LPAR during the interval. Divide by SMF70_PowerReadCount to retrieve the average power measurement of the interval. |

| 440 1B8 | SMF70_StoragePower | 8 | binary | Accumulated microwatts readings taken for storage of the LPAR during the interval. Divide by SMF70_PowerReadCount to retrieve the average power measurement of the interval. |

| 448 1C0 | SMF70_IOPower | 8 | binary | Accumulated microwatts readings for I/O of the LPAR during the interval. Divide by SMF70_PowerReadCount to retrieve the average power measurement of the interval. |

| 456 1C8 | SMF70_CPCTotalPower | 8 | binary | Accumulated microwatts readings for all electrical and mechanical components in the CPC. Divide by SMF70_PowerReadCount to retrieve the average power measurement of the interval. |

| 464 1D0 | SMF70_CPCUnassResPower | 8 | binary | Accumulated microwatts readings for all types of resources in the standby or reserved state. Divide by SMF70_PowerReadCount to retrieve the average power measurement of the interval. |

| 472 1D8 | SMF70_CPCInfraPower | 8 | binary | Accumulated microwatts readings for all subsystems in the CPC which do not provide CPU, storage, or I/O resources to logical partitions. These include service elementse, cooling systemse, power distributione, and network switchese, among others. Divide by SMF70_PowerReadCount to retrieve the average power measurement of the interval. |

| 480 1E0 | SMF70_PowerReadCount | 2 | binary | Number of power readings for the LPAR during the interval. |

| 482 1E2 | 6 | Reserved | ||

| 488 1E8 | SMF70_PowerPartitionName | 8 | EBCDIC | The name of the LPAR to which the LPAR-specific power fields apply. |

I won’t list them all, but will rather synopsise them:

- There are fields for this LPAR (the one cutting the 70-1 record). There are also fields for the whole machine.

- There are fields for CPU, memory, and other things.

I hope this synopsis is easier to consume than the table.

Some Thoughts

The term “Sustainability Metrics” is not mine; It’s part of the whole Sustainability effort for z17, which is genuinely a big leap forwards. In reality the metrics are about power consumption.

In the Marketing material it is suggested you can use this support to break down power consumption to the workload element level. You might do this for such purposes as billing, or to support tuning efforts. There are no power metrics in SMF 72-3, 30, 101, 110 etc. The name of the game is prorating, or ascribing power consumption in proportion to usage.

Prorating

Prorating for CPU is relatively straightforward; All those records have CPU numbers. There is, of course the question of capture ratio. This applies from 70-1 to 72-3 and on down.

Memory is more tricky:

- from SMF 71 down to 72-3 mostly works, though swappable workloads tend to be under represented in 72-3. This mainly relates to batch, but also TSO. Also, which workloads should things like CSA be ascribed to?

- SMF 30 real memory numbers are generally unreliable.

- Often the main user of memory is Db2. How do you apportion this memory usage?

The above is not new. The answer is not to be too pristine about it. However questions of billing and sustainability are ones where the pressure to be accurate or fair is keenly felt.

A Complete Picture?

As I mentioned just now, the data is for this LPAR, and the whole machine. There is no mention of other LPARs. This is clear from the fields being in the CPU Control Section, rather than in the Logical Partition Data Section. This choice relates to the source of the numbers: It comes from a Diagnose instruction that reports to the LPAR in this way.

So how to proceed in getting a LPAR-level view?

- For z/OS LPARs collect SMF 70-1 from all of them, even the small ones.

- Subtract the total of these from the machine-level number – for each metric.

- What’s left has to be viewed as one item: Other LPARs.

- Some other operating systems, notably z/VM, provide their own metrics. Some, notably Coupling Facility, don’t.

Generally I expect that to get you a good breakdown for z/OS and probably an aggregation for the rest, with power that can’t be attributed to any LPAR on top. That’s going to be a nice pie chart or perhaps stacked bar graph.

The Big Unknown Is How It Behaves

I wrote “a nice pie chart or perhaps stacked bar graph”.

This is real live instrumentation, rather than static estimates. One clue is in the inclusion of a sample count field. (The comments for many of the other fields suggest dividing by it.)

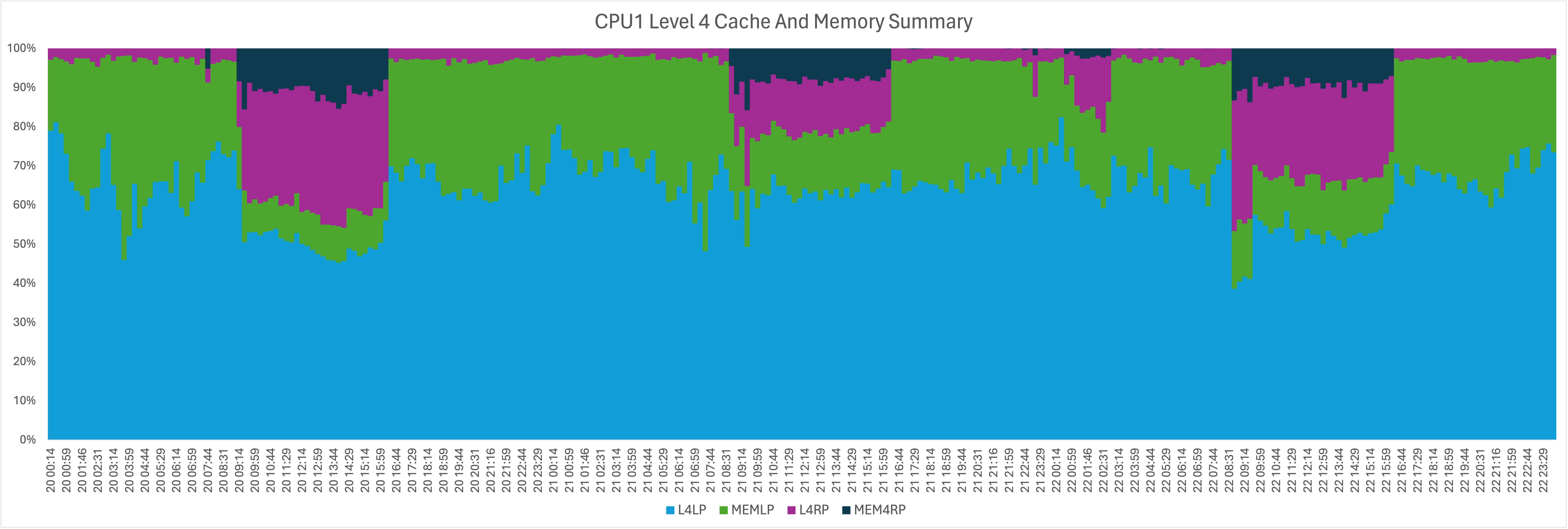

As such I expect power consumption to be shown to vary with time, and not just on configuration changes. I would hazard variation would be greater for CPU than eg memory, but I could be wrong. Hence my hoping for meaningful stacked bar graphs. And a summary for a shift could well be done as a pie chart. I will have to experiment with those – first in a spreadsheet and second in our production code.

Conclusion

It’s very nice to have time-stamped power consumption metrics. But what do I know? I haven’t seen data yet. When I do I’ll be sure to share the continuation of this journey. In the meantime what I’ve written above is the things that are obvious to me already.

This is a classic example of “we never had this data before”. I would expect it to be carried through to future machines. If so we can all see the difference when you upgrade beyond z17. I can see that being fun.

And this data is a salutary reminder of the importance of collecting RMF SMF data from all activated z/OS LPARs, especially 70-1.

Making Of

I’m writing this on a flight to Istanbul to see a customer. Nothing remarkable in that.

What is new is the return to using an iPad Mini. Long ago I had the first one released. It’s a nice size for a tray table in Economy I got a new one, along with keyboard case.

What’s new about this one is it supports a Pencil Pro. The keyboard case has a nice recess to keep the pencil safe. (Normally I world just stick the pencil on top of the iPad Mini – but this is better for travel.

I tried writing with the pencil but:

- My handwriting isn’t very tidy.

- Turbulence makes that worse. (I have direct experience of this.)

- Lots of the terms I’ve used are technical, such as”LPAR” and “SMF”.

- So it’s been a mixture of typing and writing with the pencil.

So it’s been a challenge – for the kit and for me. The palliatives are twofold:

- Me to write more tidily, probably more slowly. Good luck with that one. 😀

- Me to write some automation to fix some of the glitches. That will be fun as I’m writing using Drafts which has great JavaScript-based automation capabilities.