(Originally posted 2013-03-29.)

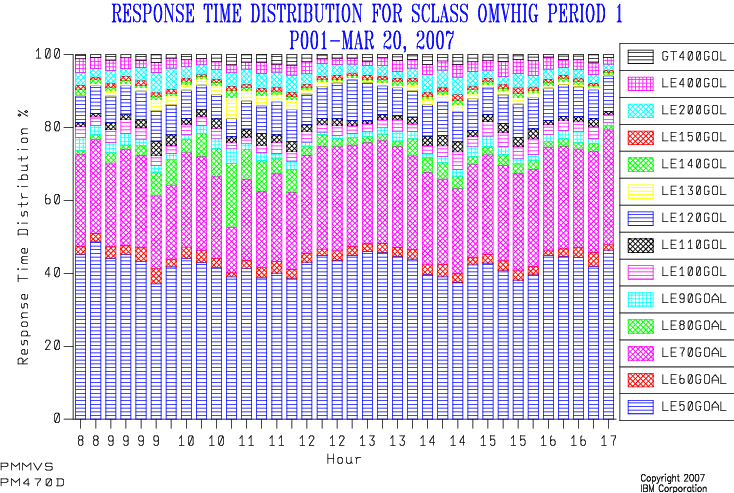

As you will’ve seen in WLM Response Time Distribution Reporting With RMF I’ve been thinking about WLM Response Time goals quite a bit recently. And this post continues the train of thought.

It’s very easy to think of WLM Service Classes as being self contained. For many that’s true – and only their own performance numbers need to be considered for us to understand their performance.

For other Service Classes it’s different: They serve or are served by other Service Classes, as shown here:

This relationship is interesting and it forces us to think beyond Service Classes as autonomous entities.

So the first part of the journey was adding some information about how one Service Class serves another in the heading of the chart I discussed in WLM Response Time Distribution Reporting With RMF

Here are three examples from one customer’s set of data:

This one – obviously for DDF – is an example where a Service Class (in this case DDF001) is Served by another (STC003).

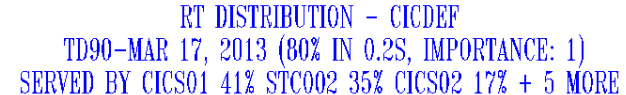

In this case the CICDEF (obviously CICS) Service Class is served by 8 Service Classes, of which 3 are significant (the other 5 providing 7% of the “servings”).

In this final case there is no serving Service Class -which I presume to be normal for OMVS (Unix System Services).

But where did I get this Service Class relationship information from?

In the RMF-written SMF 72–3 record there is a section called the Service Class Served Data Section. This section has only two fields:

- Name of the Service Class being served (R723SCSN)

- Number of times an address space running in the serving Service Class was observed serving the served Service Class (R723SCS#)

Now, you probably don’t need to know the field names – and in any case they’re probably called something different in whatever tools you’re using.

The important thing is that you can

- Construct a table relating serving Service Classes to those they serve. And hence digraphs like the one towards the top of this post.

- Get a feeling for which relationships are the most important.

But there’s a caution here:

Originally I thought R723SCS# “looked a little funny”. 🙂 After this many years of looking at that data you get hunches like that. 🙂

In this case “originally” means “on and off for the past 15 years”. Indeed there has been at least one APAR to fix the value of this field. But bad data is not the issue…

I turns out it’s not what I thought it was: Transaction rates. It’s actually samples. If the transactions are longer you get more samples.

So, you have to treat the number with a little caution, but only a little: A high value of R723SCS# probably does mean a strong connection. So those chart headings aren’t really misleading.

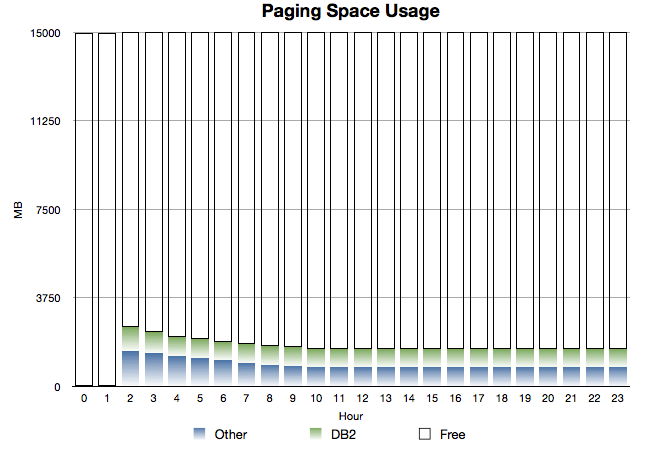

One other thing: I saw cases where the Service Class serving contained DB2 (WLM-Managed) Stored Procedures.

Digging A Little Deeper

So that was as far as SMF 72–3 took me.

And then I started this weeking concentrating on writing “Life And Times Of An Address Space”, (abstract in A Good Way To Kick Off 2013 – Two UKCMG Conference Abstracts).

Two themes have emerged from it:

- Who Am I? – About identifying what an address space is and is for.

- Who Do I talk To? – About address spaces this address space talks to.

If you conflate these and squint a bit 🙂 you come to the conclusion it’d be very nice to understand which Service Class(es) an address space served. For example, a DB2 DIST address space supports DDF transactions in different Service Classes, using independent enclaves.

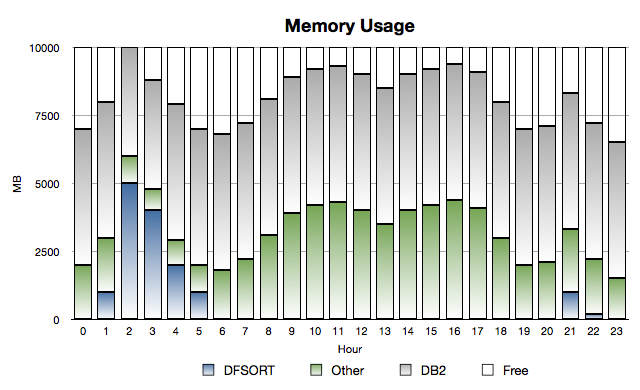

I have nice examples of how this can be examined in one of my recent sets of data. Here’s one:

Address Space DB3TDIST (obviously DDF from the name if not the z/OS program name DSNYASCP) is seen to have 20.6 independent enclave transactions a second from SMF 30 (field SMF30ETC). For the same time period three DDF Service Classes complete 20.6 transactions a second between them:

- DDFALL (misleading name) does 8.8.

- DDF001 does 0.0.

- DDF002 does 11.8.

And this was summarised over several hours. Drilling down, timewise, an tracking this over several 30 minute intervals – the SMF interval at which 30s are cut in this environment – the correspondence holds true.

(You can, by the way, see Independent Enclave CPU service units and transaction active time in the same Type 30 records.)

Admittedly this is a guessing game – but a good one.

It’s a good one because it fills in a bit of the puzzle of how a system fits together. And I include it because it is very much in the spirit of serving Service Classes.

There’s one other reason:

SMF 30 and 72–3 often don’t agree – where there’re Address Spaces serving independent enclaves. This kind of analysis helps square that circle. (They do agree in fact: They’re just looking at different things sometimes.)

But where can this technique be applied? And where can’t it?

- In addition to DDF, Websphere Application Server (WAS) plays the same game: In the same set of data I see a pair of WAS address spaces whose independent enclave transaction rates match that of the WASHI Service Class.

- Again in the same set of data I see CICS. Here, Type 30 for the CICS regions doesn’t provide transaction counts.

- I’m guessing that IMS looks like CICS in this regard. I also think there are other kinds of address space like the DDF and WAS cases, but I wouldn’t know what they are.

As I look at more sets of data no doubt I’ll find more examples in both camps.

If all you want to know is how many transactions flow through an address space you’ll need in the CICS, DB2, IMS and MQ cases to use their own instrumentation.

In fact, for DDF, there’s a nice field in DB2 Accounting Trace (SMF 101) – QWACWLME – which gives you the Service Class. But this is something you’d rather not have to work with: Nice because it gives you extra granularity but at the cost of having to produce and process SMF 101 records.

You’ll’ve spotted the address space to Service Class relationship isn’t necessarily 1 to 1 (in either direction) so that potentially makes the guessing quite difficult.

To anyone who’s thinking “but I know all this, after all it’s my own installation so I know what’s running in it” I have to politely 🙂 and rhetorically ask “do you really?” One of the slides in “Life And Times” (L&T for short) has the title “Let’s Treat An Address Space As A Black Box”.

I think that’s right, actually: It gives us a good framework for really getting to know how our systems work a lot better, with the minimum of effort. After all, there’s limited time for you to manage your systems (and for me to get to know them). And if you ever move from one installation to another (as I effectively do) you’ll probably feel the same way as I do: There’s a premium on getting to know the installation as quickly and as well as possible.

It’s been an interesting line of enquiry: As with so many other cases, unless you’re prepared to just accept the reporting you’ve been given, life is very much like taking a machete to the jungle and occasionally you find a gem. But sometimes you just find yourself cutting a circular path. 🙂

And now I just want a magical guessing machine. 🙂 Actually it’s something I’m hoping to raise with IBM Research.