(Originally posted 2012-11-19.)

With apologies to cat keepers everywhere (of whom I’m one). 🙂

Most of my reporting – when not graphical using GDDM – is created using Bookmaster. This looks in many ways like HTML and is another declarative markup language for text.

It used to be what most IBM publications (including Redbooks) are written in. And customers bought Bookmaster (and DCF / Script/VS), embedding it into the document-creation portion of their applications.

To modernise this kind of document creation you could rewrite, generating PDF or HTML. I’d like to suggest there’s an alternative, one that is evolutionary and might not require much change to your original programs. In fact probably none to existing code.

You can use B2H (described here) either on z/OS or on a PC to convert Bookmaster (Bookie to her friends) or some kinds of DCF Script to HTML.

I use B2H on Linux, using Open ObjectRexx, though I also have it installed on my z/OS system.

You could stop there – with HTML – but you’ll see in a second why I think you shouldn’t.

Motivation

Consider what you get if you run Bookmaster source through B2H:

This is a pair of tables, with no augmentation and without any styling.

Now consider:

This is the result of applying some elementary styling (including a box shadow from CSS3). Doesn’t it look better?

I won’t claim to be the most experienced CSS user but this little sample shows some of what can be done.

(CSS or Cascading Style Sheets is the modern evolving standard for styling HTML, with increasingly good compliance from the major browser makers.)

One nice thing about the approaches I’m outlining here is that you can largely separate styling from content: Normally we would speak of content developers having different skills and concerns from web designers – and CSS is what the latter would use (and other technologies such as Javascript and Dynamic HTML (DHTML) and so on).

In this case the content developers might not exist any more: The application code is decades old.

So this separation is especially valuable here.

How To Get There

The HTML that B2H creates is fairly old-fashioned, though you can influence some aspects of its generation.

For example, it probably wouldn’t pass a formal parsing test. But most browsers will happily render it – and create an acceptable Document Object Model (DOM) tree.

Creating a DOM tree is important, as we shall see.

As I showed above one can do nice things with CSS, and even more with CSS3.

But how to inject it?

There are are several ways.

Here’s one that doesn’t require any change to the source file:

B2H allows you to define a profile.

The default one has a name which is a variation on B2H.profile.

But you can override this with the USERPROF option when you invoke B2H.

If you do so you can place lines like the following in this user profile:

headrec.text='H2 { font-size: large; color: blue }'

This will inject a line into the HTML <head> element.

You can place as many of these as you like in the user profile.

(This one is just a fragment of CSS, of course.)

The actual CSS for the above example, by the way, is:

table

{

background: #DDDDFF;

border-collapse: collapse;

border: 2px solid black;

box-shadow: 10px 10px 5px #888888;

}

th

{

font-weight: bold;

background: #BBBBFF;

}

Suppose You CAN Change The Program That Creates Bookie

This is probably the best place to inject stuff that affects how B2H operates.

Within a psc tag bracket you can inject HTML and this will only affect B2H processing. For example:

:psc proc='html'.

.*B2H HTML <img src='/myimage.png'/>

:epsc.

I actually use this one in my code – to inject disk and tape icons above descriptions of disk and tape controllers. (Not very pretty icons but good enough to remind which I’m dealing with.)

Another good use would be to inject some CSS, either inline or referring to an external file.

You can also inject stuff into the HTML <head> element without an external profile.

To rework the example that used a user profile, consider the following.

.*b2h option headrec.text='H2 { font-size: large; color: blue }'

This has the same effect – and is simpler because it doesn’t require a user profile.

One other thing you might want to try is “wrapping” an element generated by B2H.

Consider the following:

:psc proc='html'.

.*B2H HTML <span id='myTable'>

:epsc.

:table …

⋮

:etable.

:psc proc='html'.

.*B2H HTML </span>

:epsc.

This wraps an entire HTML (as it will become) table in a span. (You could do it with a div though this would probably change the layout.)

The span element has an id so the table can be readily referenced in CSS.

This technique is also useful with Javascript.

What If You Want To Work With Document Content?

In my code I actually do want to work with the document content.

In particular I update the title element – as the original Bookie doesn’t have the title I want.

(In Firefox this appears on the tab and I’ve taken steps to make this mnemonic and succinct.)

The answer in most cases is to inject some Javascript.

I’ve already shown you ways of doing this.

I would recommend – where possible – you reference an external Javascript file, rather than adding the code inline.

(The same would be true of CSS.)

But here’s another technique – which my code actually uses:

I use XMLHttpRequest (XHR for short) via the Dojo framework to load the HTML created by B2H and on load I invoke a Javascript function to modify the web page.

My code looks quite like this:

function handleLoadedBookie(response,reportName) {

// If first row has a TD in it then that must signal a tdesc so stick classname of "tdesc" on it

// NOTE: CSS expects that class and uses it to bold the text.

tdescTables=dojo.query("table").filter(function(x) {

possibleTD=x.childNodes[1].firstChild.childNodes[1]

if(possibleTD.nodeName=="TD") {

// Flag with tdesc class so CSS can pick up on it

possibleTD.className="tdesc"

// Filter returns this node

return true

}

else {

// Filter throws away this node

return false

}

})

}

// Runs when DOM loaded

function onready(){

dojo.xhrGet({

preventCache: true,

url: '/studies/ClientA/ClA1012/A158/03 OCT P/LPAR.html',

error: function(response,ioArgs){

alert(response)

},

load: function(response,ioArgs)

{

dojo.query('body').addContent(response)

handleLoadedBookie(response,'LPAR')

}

})

}

I’ve extracted from my actual code and I’m not going to describe what it’s doing in detail because many people won’t be using Dojo.

The fundamental calls you would use in Javascript to manipulate the DOM tree (and hence the page) are:

- getElementById –

which returns the element whose id matches the parameter passed in.

(Which is why I mentioned id just now – with reference to wrapping.)

- getElementsByTagName – which returns an array of elements whose tag name is passed in. e.g. “tdesc”.

You could use this either to apply a change to all elements with the same tag name or to perform logic like “get me the third table in the page”.

Of course there are many ways of using Javascript to manipulate a web page – via its DOM tree.

But it’s beyond the scope of this post to describe them.

A competent Javascript programmer (and I “play one on TV” 🙂 ) will be thoroughly conversant in this area.

But here are a couple of pointers:

- You can use Javascript to attach event handlers to elements and so add interaction.

- You can use Javascript to manipulate the content of the web page, such as totalling columns in a table.

Really quite powerful stuff.

What If You Don’t Want HTML?

Here I’m a little hazy as I don’t actually do this.

I break down the problem into two parts:

- Exporting the content.

- Producing a facsimile of the page, styling and all

The latter I know can be done in Firefox with the PrintPDF Extension.

I tried it and it looked good.

I tried other extensions that somehow use a web service to point at your data’s URL.

That didn’t work for me as I’m not exposing my data to the web.

Actually there’s such a wide range of things you might want to do with Bookie documents once converted to HTML that this part of the blog couldn’t cover a significant proportion of them.

So I’ll you ask you, dear reader, what you do with HTML.

Conclusion

I’ve shown you some ways you can use the HTML produced by B2H and some post-processing to modernise documents produced by programs that used to produce Bookie source.

I would say these techniques, rather than attempting to parse the HTML by some other programmatic means (whether PHP, Python or Java, or something else) are straightforward.

Indeed it would take a most liberal HTML parser in any of those languages (which do exist, at least in some of them) to handle the HTML that B2H generates.

Fortunately most web browsers are very liberal.

Unfortunately I’m not aware of a “headless one” i.e one that does everthing in the background.

(I don’t think CURL could help here, but I’d love to be proven wrong.)

In case you’re wondering why we ever used Bookie in the first place, it’s because we used to generate real paper books – with all our graphs and tables in.

But now I never print anything out:

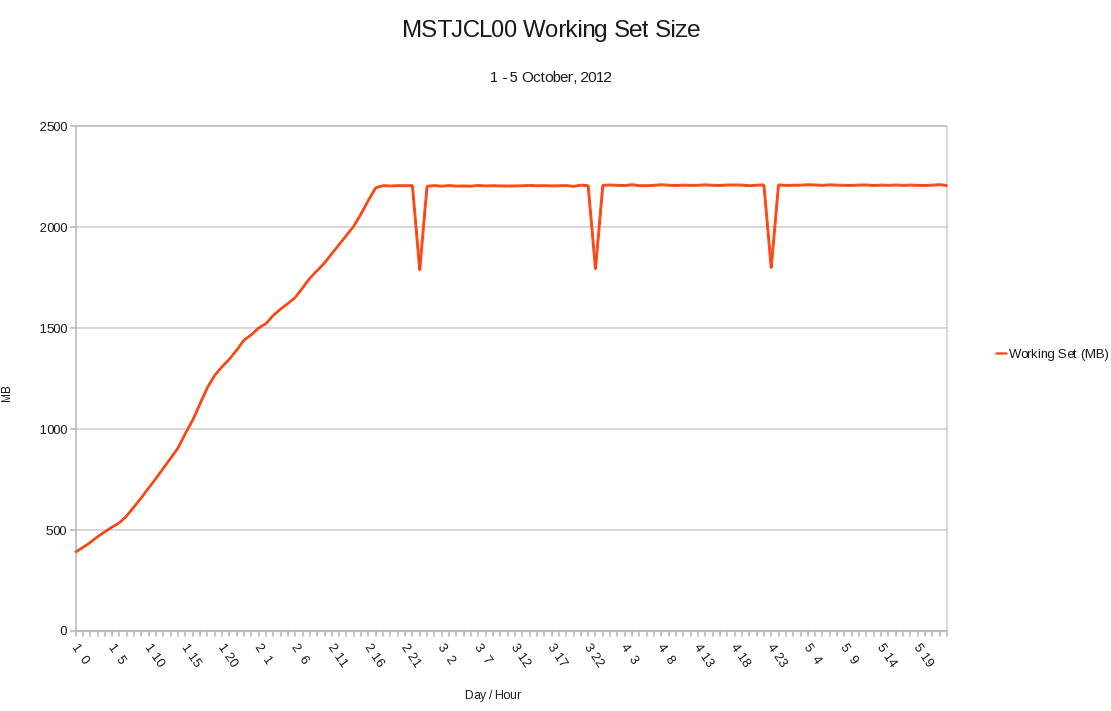

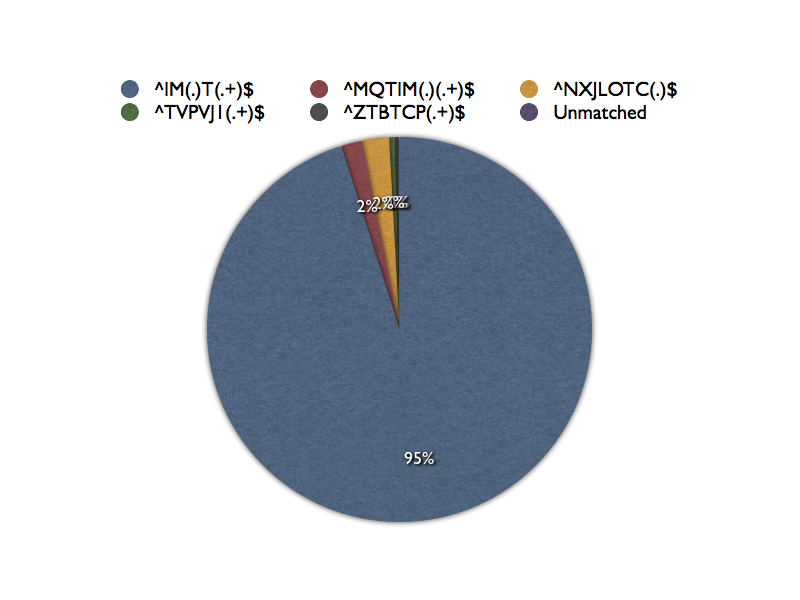

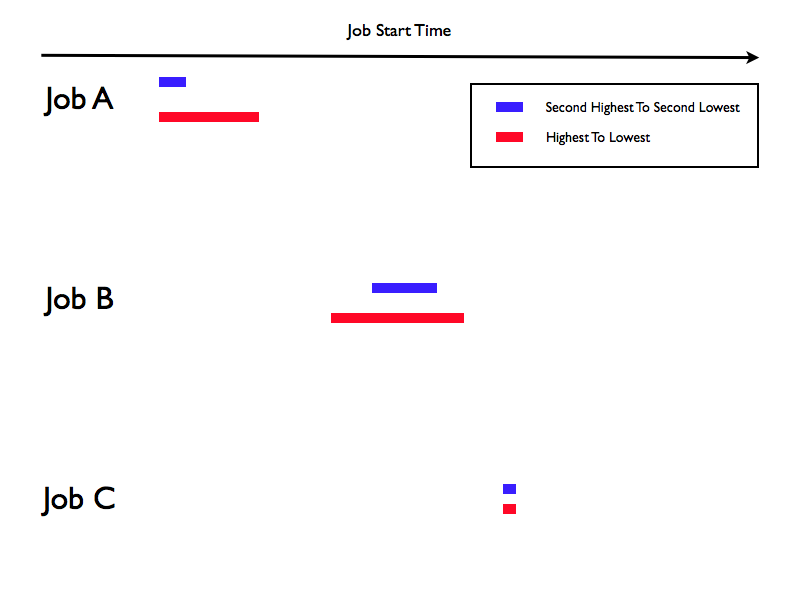

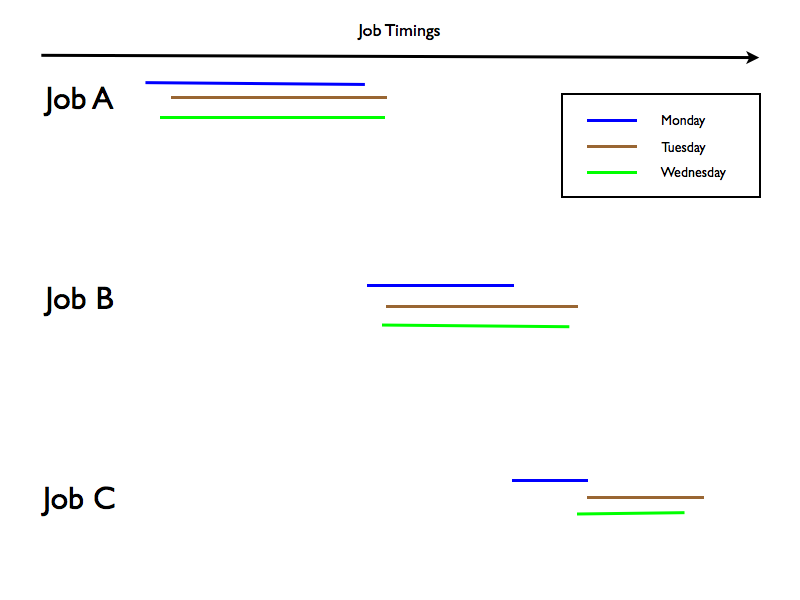

All my presentations are done using GIFs created via GDDM (for the graphs) and sometimes captures of the tables (generated by Bookie and B2H).

If you see me pop up a web browser when I’m presenting to you I’m either fumbling for the GIFs or else the Bookie reports – courtesy of B2H and some of the tricks I’ve outlined in this post.

So, you can revive good things written in Bookie with B2H, and you can breathe new life into them with some of the techniques in this post.

And you can see some of the reason why my misspent middle-age was misspent with CSS, HTML and Javascript. 🙂