(Originally posted 2015-04-11.)

It’s more like someone rich lighting their cigar with a hundred dollar bill. 🙂

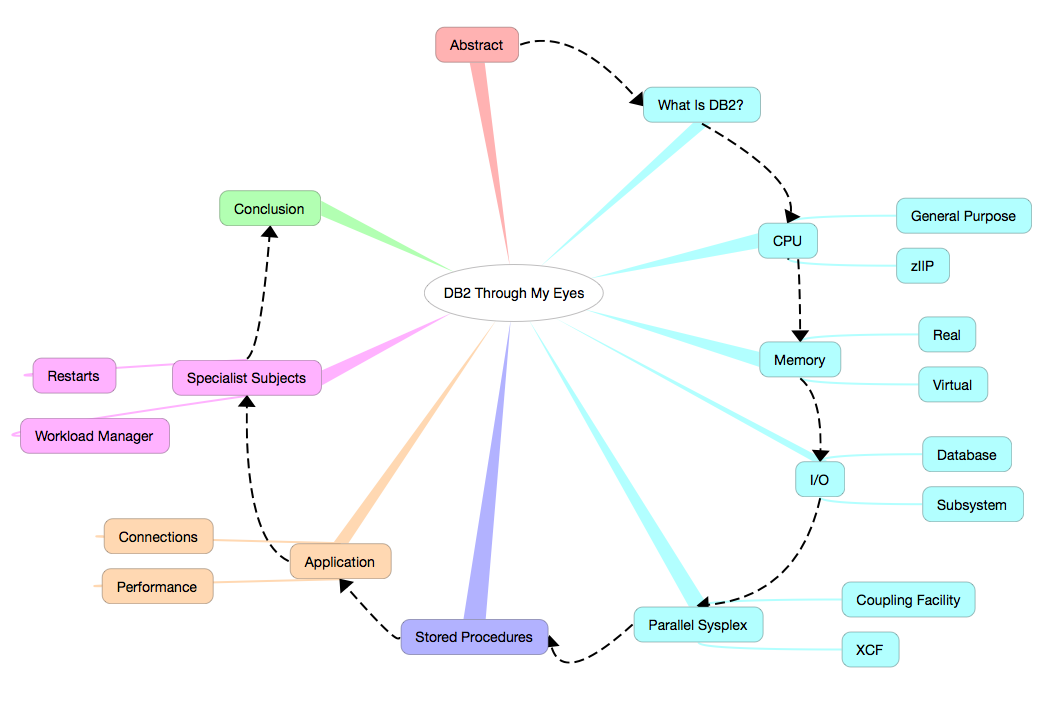

Seriously, this post is about Coupling Facility Lock Structure False Contention and why it matters. It is, of course, inspired by a recent customer situation.

Before I explain what False Contention is, and then go on to talk about its impact and instrumentation, let me justify the title by asserting Lock Contention does not ultimately cause locks to be falsely taken nor ignored. But you probably don’t want it anyway.

What Is False Contention?

Lock structures are used by many product functions, such as IMS and DB2 Data Sharing, VSAM Record-Level Sharing, and GRS Star. As the name implies they’re used for managing locks between z/OS systems.

A lock structure contains two parts:

- A lock hash table (called the lock table)

- A coupling facility lock list table (called the modified resource list)

The lock hash table can contain fewer entries than there are resources to manage. The word hash in the name reflects there being a hashing algorithm between locks and lock table entries.

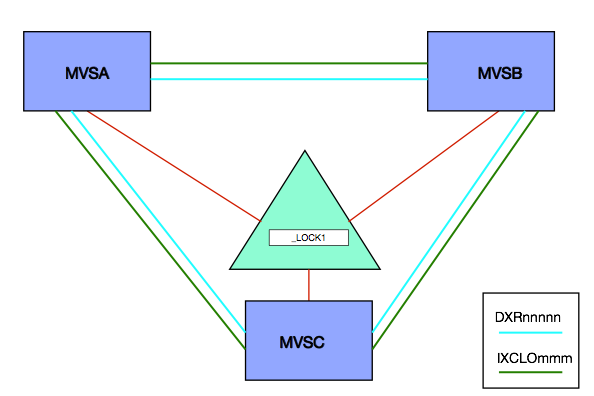

For each lock structure there is at least one XCF group associated with it – whose name begins with IXCLO. For some lock structures the owning software (middleware) has a second XCF group.

When a resource is requested it is hashed to a particular lock table entry. Potentially two or more resources could hash to the same lock table entry. They are said to be in the same hash class.

If it appears a resource is unavailable (the lock appearing to already be taken) XES must resolve whether this is true or not. So XES uses the IXCLO XCF group for the structure to resolve the apparent contention:

- If this XCF traffic indicates the lock is truly taken this is called an XES Contention.

- If the result of this traffic indicates this is not a true contention (but rather the result of two resources hashing to the same lock table entry) this is deemed a False Contention.

Statistically, the larger the set of lock resources being managed relative to the number of lock table entries the greater the chance of False Contention.

What Harm Does False Contention Do?

As I said above, False Contention doesn’t distort the management of locks from the point of view of the middleware or the applications.

So its harm is limited to causing additional XCF traffic. The main effects of this are:

- Higher coupled (XCF address space) and coupling facility CPU.

- Higher use of the XCF signalling infrastructure, such as Channel-To-Channel (CTC) links and coupling facility paths.

How Can You Detect False Contention And Its Effects?

You can see effects with RMF in both the Coupling Facility (74–4) and XCF (74–2) records.

Coupling Facility

Each lock structure is instrumented in each systems’ 74–4 record. [1] Though some things are common to all systems – such as the structure size – some things are system-specific, such as the traffic from the system to the structure.

In particular, the rate of requests, those leading to XES Contention, and of False Contention are available. Keeping the False Contention rate small relative to the request rate and, even more so, relative to the XES Contention rate is a sensible goal.

XCF

For Integrated Resource Lock Manager (IRLM) exploiters there are two XCF groups associated with the lock structure – the one whose name begins with IXCLO and another whose name begins with DXR. [2]

For the others I’ve worked closely with there is just the IXCLO XCF group. The IRLM case is illustrated below:

You can measure (with SMF 74–2) the traffic in the IXCLO and DXR groups (though the latter has nothing to do with False Contention). [3]

You can, of course, see how much CPU in the Coupling Facility is used to support a specific XCF List Structure. Likewise you can see the effects on XCF CTC links.

Perhaps less usefully, you can measure the CPU used by the XCF Address Space on each system – using SMF 30 (2,3) Interval records or a suitably set up Report Class using SMF 72–3 (Workload Activity). I say “perhaps less usefully” because most of the time the IXCLO and DXR groups’ traffic is dwarfed by that of e.g. DFHIR000 (Default CICS).

How Might You Easily Reduce False Contention?

Generally the answer is to increase the number of lock table entries in the lock structure. The most obvious way of doing this is to increase the lock structure size, though this might not be entirely necessary:

The size of each entry in the lock table can be managed. Its size is dependent on the value of MAXSYSTEM when the structure is (re)defined. A value less than 8 results in a 2-byte entry, whereas 8 to 23 is 4 bytes and above that it’s 8 bytes.

Only a few of my customers need more than 23 connecting systems. But many have a need for 4-byte entries.

You can, with sufficient memory in the Coupling Facility, define a bigger lock structure, so the technique of reducing the lock table entry size is best reserved for when structure space is at a premium.

Conclusion

Practically installations tolerate some level of False Contention, with the concommitant XCF traffic that tends to entail, but generally you want to minimise it to the extent you can.

Hopefully this post will’ve given you some motivation for monitoring lock structure False Contention. And explained how you might deal with it.

Here, by the way, is a very nice blog post from Robert Catterall: DB2 for z/OS Data Sharing: the Lock List Portion of the Lock Structure .

This post brought to you by (NSFW) Loca People which should probably be my theme tune. 🙂

-

In the case of a (System-Managed) Duplexed lock structure each copy appears separately – though they behave identically. ↩

-

The DXR XCF group is used by IRLM to further refine the locking picture. IRLM has a more subtle collection of locking states than XES. This traffic is used to determine whether a XES lock conflict (XES Contention) is a lock conflict from IRLM’s point of view (IRLM Contention. Its volume has nothing to do with False Contention. ↩

-

Also perhaps irrelevant is field R742MJOB which gives the address space name of the XCF member, in this case the IRLM address space. ↩