(Originally posted 2017-06-25.)

Back in 2009 I wrote about Performance of the (then new) DFSORT JOIN function.

This post is just a few notes on things that might make life easier when developing a JOIN application. Specifically the one I alluded to in Happy Days Are Here Again? when I talked about processing SMF 101 (DB2 Accounting Trace) records.

And I wrote it having scratched my head for a few hours developing a JOIN application that will soon be part of our Production code.

Lesson One: Massage The Input Files In Separate Steps

This flies in the face of what I said in 2009 but bear with me. That post was about Performance in Production. Here I’m talking about Development, specifically prototyping.

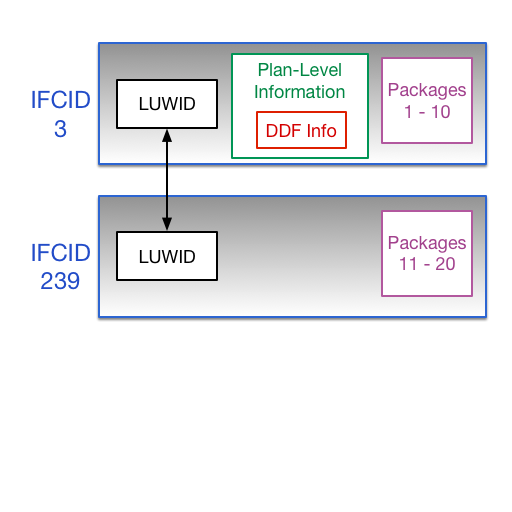

Here is what “Single Step” looks like:

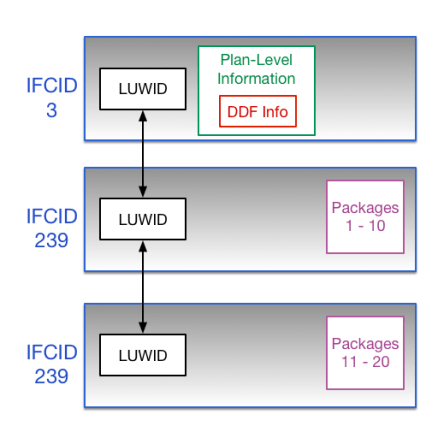

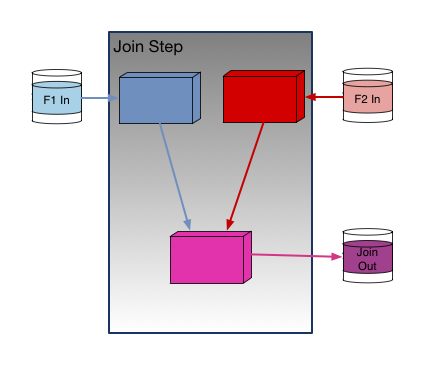

And this is what “Multiple Step” looks like:

The clear advantages of “Single Step” are:

- There is no need for intermediate disk storage (and I/O).

- It is simpler.

But sometimes you really want to know what the intermediate records look like. In particular what positions fields end up in, what lengths they have, and what formats they appear in.

And you can always move the logic to the JOIN step as you approach Production; In fact you should. SYSIN becomes JNF1CNTL for file F1 and JNF2CNTL for file F2.

Viewing Intermediate Files While Running JOIN

While you could run these pre-processing steps and stop before the JOIN step that isn’t actually necessary. You can still see the intermediate files if you could something like

OUTFIL FNAMES=(SORTOUT,TESTOUT)

and route TESTOUT DD to SYSOUT (or wherever). The SORTOUT data set can then be fed – as you originally intended – into the JOIN step.

In my case the two data sets fed into the JOIN are temporary; When the job completes they’re gone.

Lesson Two: Debug Failed Joins One Field At A Time

When I was developing my JOIN I had two unexpected (and wrong) things happening:

- I got zero records out.

- I got far more records than expected out.

Zero Records Out

This is the case where there were no matching records, or so it seemed.

In my application I’m joining on multiple key fields – 8 in my case.

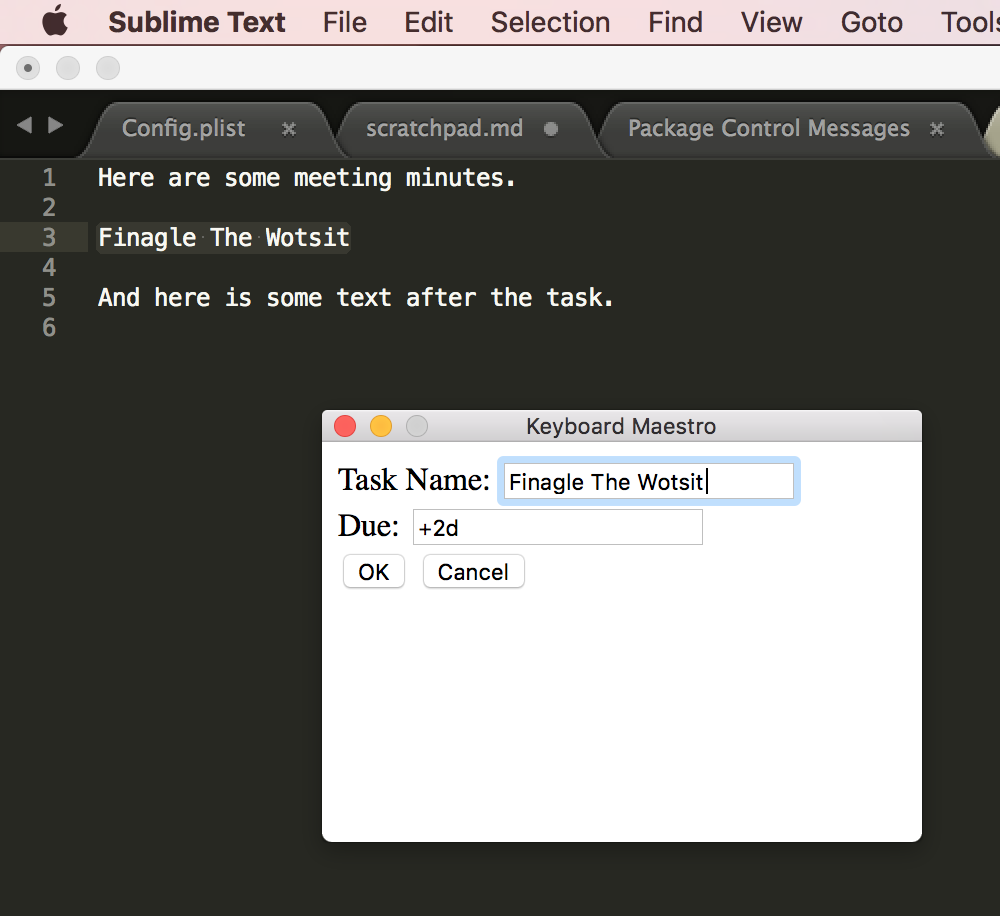

Having got very confused for a while[1], I took the following approach:[2]

- Try matching on one field.

- If that doesn’t work, p out why. And fix.

- Repeat with that field and another.

- And so on.

By the way it’s probably best not to direct the output to the SPOOL; While I was debugging this way I was sending several million lines there before I caught and purged the job.

Far More Records Than Expected Out

This one was a little more difficult to debug. The net of it is the JOIN key – all umpteen fields of it – isn’t long enough (specific enough).

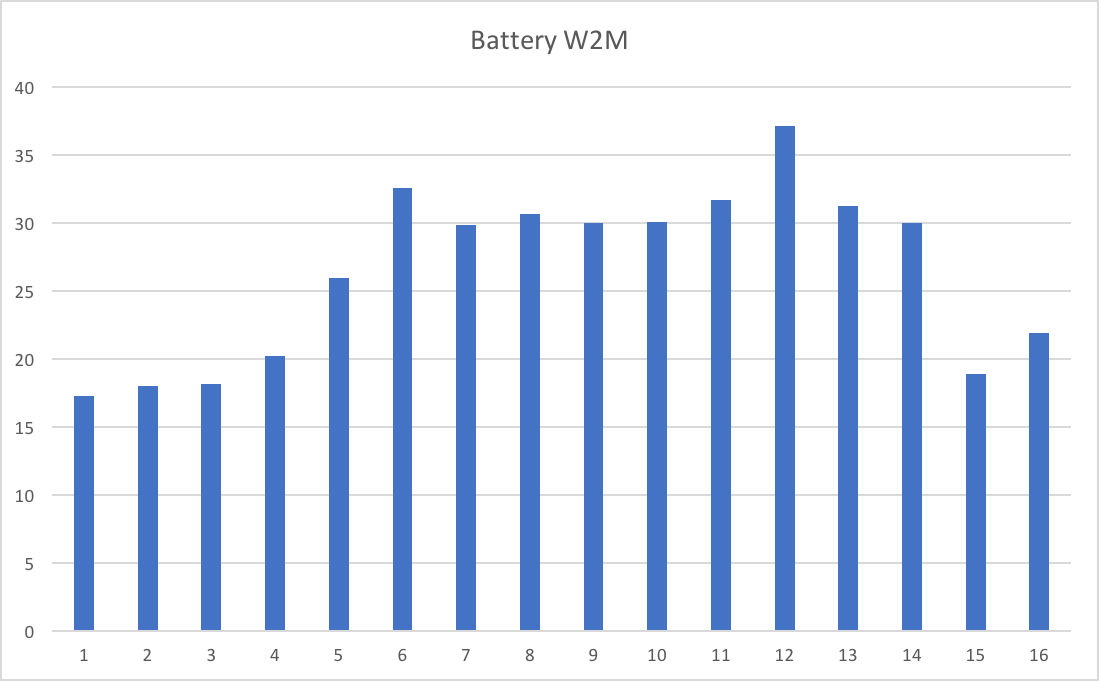

In my case I was using the first 22 bytes of the 24-byte Logical Unit Of Work ID (LUWID). And I was getting orders of magnitude more records out than I expected.

The final two bytes are a commit number. For some reason I thought it shouldn’t be part of the join key. I was wrong.

Extending the key to 24 bytes made the JOIN (demonstrably) behave.

Lesson Three: Careful With The Name Spaces

DFSORT doesn’t really afford multiple name spaces, so you have to fake them.

So for the F1 file you might prefix the symbols with “F1_” and, similarly, the symbols for the F2 file might begin with “F2_”.

Conventionally, I use “_” before the symbols that map a record after INREC. You could adapt that so the results of REFORMAT could be mapped using symbols prefixed with “_”.

In any case some sort of symbol scheme is needed.

While we’re talking about symbols, I wouldn’t attempt JOIN without them.

If you’re developing with the “Multiple Step” approach you can reuse the symbols between the reformatting and JOIN steps – because you can concatenate SYMNAMES data sets. But note this reusing the output symbols from the reformatting steps for the input to the join.

One thing you can’t do is specify different SYMNAMES DDs for the pre-processing stages in the “Single Step” case. So you have to be careful with names.

In case the above is clear as mud let me try a little example.

In F1 Step you might code:

//SYMNAMES DD DISPLAY=SHR,DSN=HLQ.F1.INPUT.MAPPING

// DD *

POSITION,1

F1_A,*,16,CH

F1_B,*,8,BI

/*

And for the F2 Step you might code:

//SYMNAMES DD DISPLAY=SHR,DSN=HLQ.F1.INPUT.MAPPING

// DD *

POSITION,1

F2_A,*,16,CH

F2_C,*,4,BI

/*

In the JOIN Step you might code:

//SYMNAMES DD DISPLAY=SHR,DSN=HLQ.F1.INPUT.MAPPING

//SYMNAMES DD *

* FROM F1

POSITION,1

F1_A,*,16,CH

F1_B,*,8,BI

*

* FROM F2

POSITION,1

F2_A,*,16,CH

F2_C,*,4,BI

*

* REFORMAT OUTPUT

POSITION,1

FLAG,*,1,CH

_A,*,16,CH

_B,*,8,CH

_C,*,4,BI

* OUTREC OUTPUT

__A,*,16,CH

...

/*

Of course, in the above you’d probably put the F1_ and F2_ fields in their own symbols files – to enable reuse.

One minor annoyance with symbols files is they push you towards another ISPF session, which you could probably do without. But it is only a minor annoyance.

Lesson Four: REFORMAT Isn’t The Final Reformatting

I expected REFORMAT – which pulls the fields together from the two input streams – to allow formatting such as character strings.

It doesn’t. So you have to add them in an OUTREC or OUTFIL statement. A cumbersome alternative is to pass the fixed strings in as fields from the F1 or F2 streams.

One thing that is available in REFORMAT (and only from REFORMAT) Is a single-character indicator of how the record was matched. It has three potential values:

- 1 – only from F1.

- 2 – only from F2.

- B – from both F1 and F2.

This might prove useful In debugging. You indicate you want this flag using the “?” character.

Conclusion

So, these are the learning points from my second DFSORT JOIN application. If this looks complex I think it reflects some of the powerful complexity of DFSORT JOIN. I also think it’s fair to say complex DFSORT applications can be fiddly.

The one overarching thing in my mind is to build any DFSORT application up in simple stages, and perform optimisations later. A good example, which I’ve already shown you, is the “Multi Step” approach to building up JOIN.