(Originally posted 2014-09-08.)

Some technologies show up “in the field” very soon after they’re announced and shipped. Others take a little longer.

Back in 2009[1] I blogged about one technology – DFSORT JOINKEYS. For this post to make much sense you’ll probably want to read that post first. Here it is: DFSORT Does JOIN.

Dave Betten and I have – at last – a set of data from a customer where one of the major jobs does indeed use JOINKEYS. The purpose of this post is to show you what one of these looks like – from the point of view of SMF records.[2] I won’t claim this post highlights all the statistics available to you but I hope it gives you a flavour.

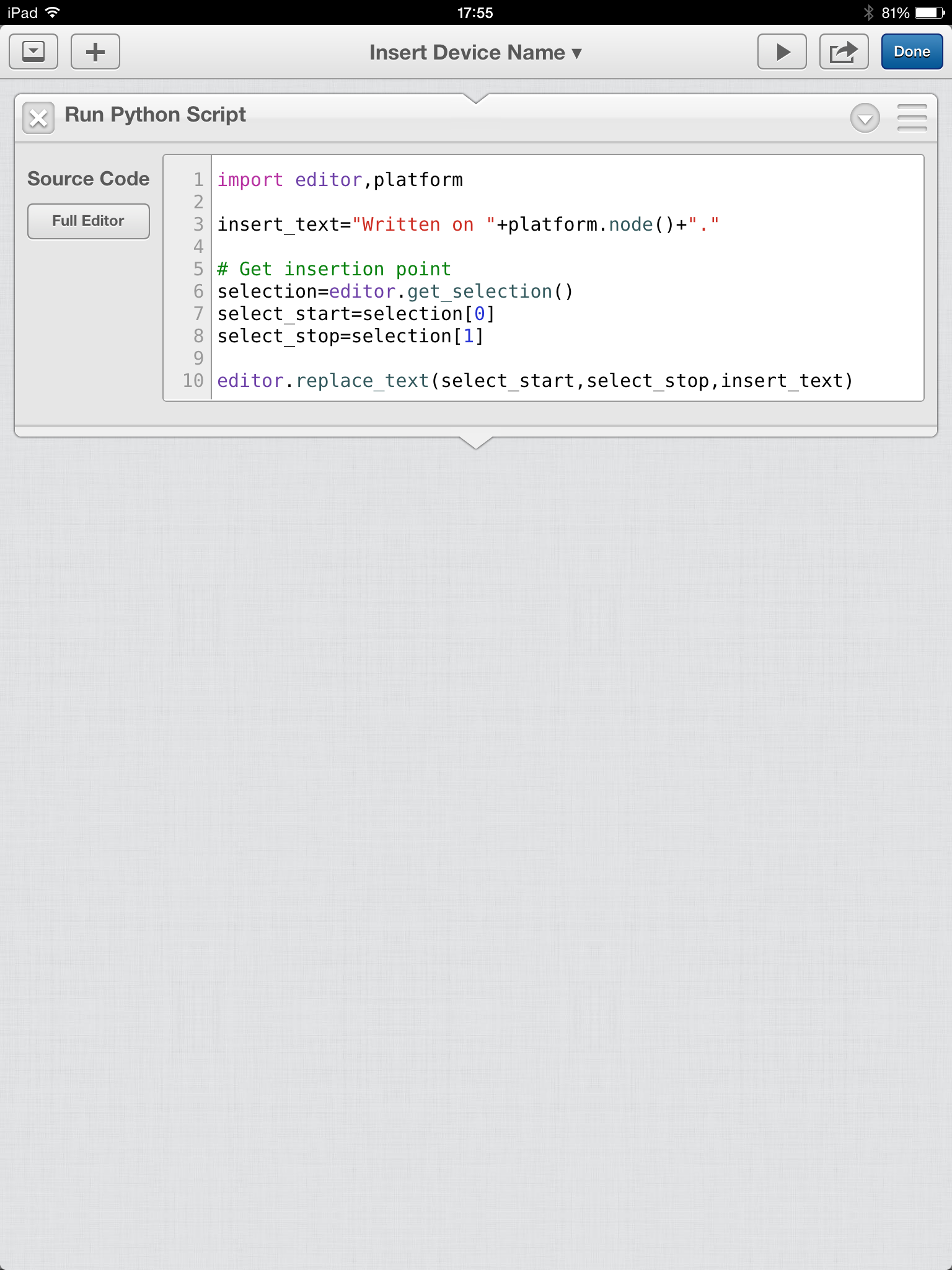

Though the job is repeated this post will concentrate on one such running. As you’ll see from the graphic below it runs from 15:25 to 16:33. There are two steps:

- A SORT invocation, running from 15:25 to 16:11.

- A JOINKEYS invocation, running from 16:11 to 16:33.

SORT Step

While the SORT step is the longer the purpose of this post isn’t to discuss how to speed up the job overall. But it’s a good “warm up”:

- In this case we can see the Input phase (marked by the timestamps for OPEN and CLOSE of the SORTIN data set): 15:25 to 15:51.

- We can equally see the Output phase: 15:51 to 16:11 (from the SORTOUT data set OPEN and CLOSE timestamps).

- We can see 22 SORTWKnn data sets were OPENed and CLOSEd, spanning both input and output phases.[3]

- We can see no Intermediate Merge phase – the Input and Output phases abutting each other.

From The SORT Step To The JOINKEYS Step

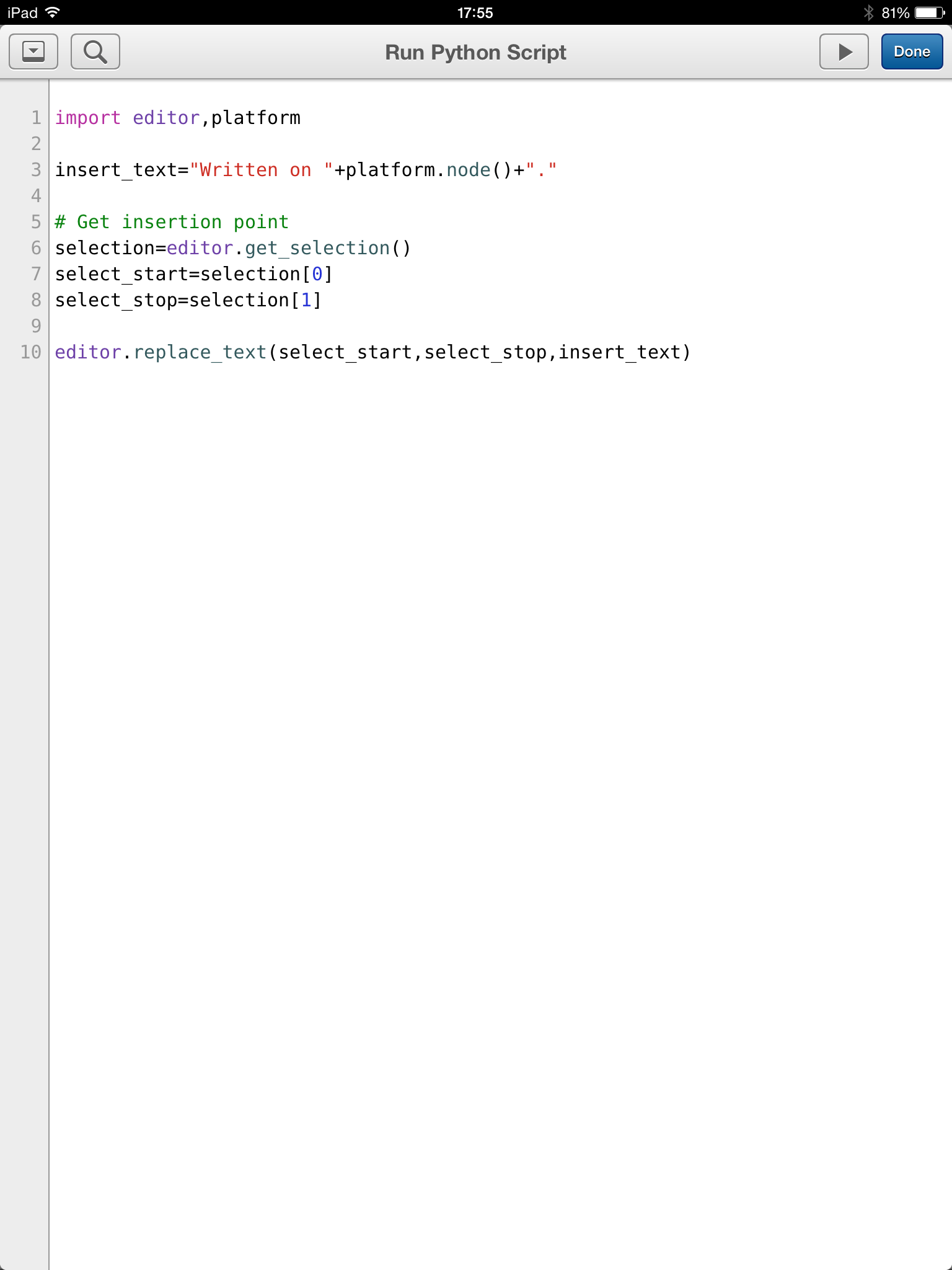

The SORTOUT data set from the SORT step feeds directly into the JOINKEYS step as the SORTJNF1 data set. Note it’s sorted twice – once in the SORT step and again in the JOINKEYS step – which seems rather a pity. It is read by a TSO user later, so maybe the two different sort orders are needed.

What I’ve just used is our Life Of A Data Set Technique (or LOADS for short). Below is the LOADS table for this SORTOUT data set.

JOINKEYS Step

This is where – to me – it gets more interesting. In this case we’re joining two data sets – DDs SORTJNF1 and SORTJNF2.

-

As you just saw SORTJNF1 came from the previous SORT step.

-

SORTJNF2 is a relatively small data set.

both data sets are sorted on the same key fields. We know this just because they each have Sort Work File data sets – 5 used in one case and 21 in the other.[4]

You might’ve spotted that everything I’ve said so far is based on SMF 14 and 15 (Non-VSAM CLOSE for Read and Update) records. Now let’s start to dig into the SMF 16 (DFSORT Invocation) records, restricting ourselves to the JOINKEYS step.

We have three SMF 16 records for this step:

-

JNF1 Sort

-

JNF2 Sort

-

Joining Copy

The two sorts are necessary because the programmer told DFSORT to sort both files so the key fields for the Join are in order. As I indicated in DFSORT Does JOIN there are ways of avoiding this if the sorts are unnecessary (and terminating if the sorts are proven necessary).

For a real tuning exercise you’d try to avoid unnecessary sorts.

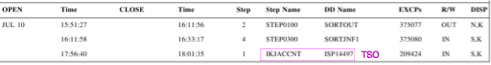

The following is a schematic of how the three invocations work.

Let’s look at JNF2 first. The 5 Sort Work File data sets OPEN and CLOSE within the same minute (16:11) according to our Gantt chart. Indeed there are zero EXCPs to them. But the SORTJNF2 data set is held open until the end of the JOINKEYS step (16:33).

Note there’s no output data set from this sort.[5] We’ll come to what happens to the output data in a minute.

Turning to JNF1 the Sort Work File data sets stay open throughout the JOINKEYS step; There’s lots of I/O to them.

Again there’s no output data set from this sort.[5]

The third SMF 16 record relates to the Copy (with an exit) that does the actual join. It has no input data sets but it does have an output data set (DD OUTFILE1).[6]

So let’s turn to what SMF 16 tells us about records and how they flow:

- JNF1 reads 179 million records from DD SORTJNF1 and passes them to a DFSORT E35 exit, writing none to disk. These records are fixed-length and each 300 bytes. The sort’s key length is 15 bytes.

- JNF2 reads 5,000,006 records from DD SORTJNF2 and passes them to a DFSORT E35 exit, again writing none to disk. The sort is for 15 bytes again, which is curious as the LRECL appears to be 11 bytes; Some padding must occur – perhaps to match the keys from JNF1.

- COPY inserts 179 million records, passing that many to OUTFIL.

- OUTFIL reduces the 179 million records to 30 million; The SMF 16 record says OUTFIL INCLUDE/OMIT/SAVE and OUTFIL OUTREC was used, which begins to explain the reduction. But the LRECL remains 300 bytes; I suspect the JOIN is to decide which records to have OUTFIL throw away, before writing them to DD OUTFILE1, and the OUTREC is to remove the extra bytes from JNF1 used in the record selection.

One other point – from SMF 14 and 15 analysis: In this case I don’t see records for SYMNAMES or SYMNOUT DDs, so either DFSORT symbols aren’t being used or they are SYSIN or SPOOL data sets, respectively. To my mind SYMNAMES data sets are most valuable when they are permanent. I don’t expect SYMNOUT to have permanent value, beyond debugging.

Conclusion

There’s lots of extra detail in the SMF 14, 15, and 16 records of course. But I hope this has given you some idea of how to view the data when JOINKEYS is invoked.

And the reason it’s taken us a while to see JOINKEYS in a customer is quite straightforward: It’s not something you flip a switch to use; Rather you have to write code to use it.

And note that this post hasn’t given any real tuning advice: The previously-mentioned blog post does. And the actual customer situation is a little more complex than this (though the facts I’ve stated are all true).

-

I would think most customers have the function installed by now, so hopefully if you like JOINKEYS it’s there for you to use. ↩

-

To replicate this sort of thing you need SMF 14 and 15 for non-VSAM data sets, 62 and 64 for VSAM, 16 with SMF=FULL for DFSORT, and 30 subtypes 4 and 5 for step- and job-end analysis. ↩

-

In preparation for writing this post I took a detour: This Gantt chart used to, rather unhelpfully, have 22 lines for these SORTWKnn data sets, each with the same start and stop times. I now feel I can use this chart in a real customer situation as rolling up the SORTWKnn data sets that indeed have matching timestamps makes it so much punchier. ↩

-

Curiously JNF1WK16 is never OPENed. Perhaps I should teach my code to detect “missing” Sort Work File data sets like this. ↩

-

Both the absence of output data sets from SMF 15 and the absence of Output Data Set sections in the DFSORT SMF 16 record confirm this. ↩

-

You only get Output Data Set sections in SMF 16 if SMF=FULL is in effect for them. ↩