(Originally posted 2016-11-13.)

Back in the Summer I talked about z13 Simultaneous Multithreading (SMT) in Born With A Measuring Spoon In Its Mouth. I shared that I was feeling my way forward, and discovering others were doing likewise.

Here we are a few months later and my code has come on in leaps and bounds.1

So I think it’s worth sharing some design stuff and a little discovery; I’m working on the principle that people have to embrace SMT on their own personal journey. 2

So let me show you a couple of graphs. I’ve obfuscated the system names on the graphs but otherwise they are “live”.

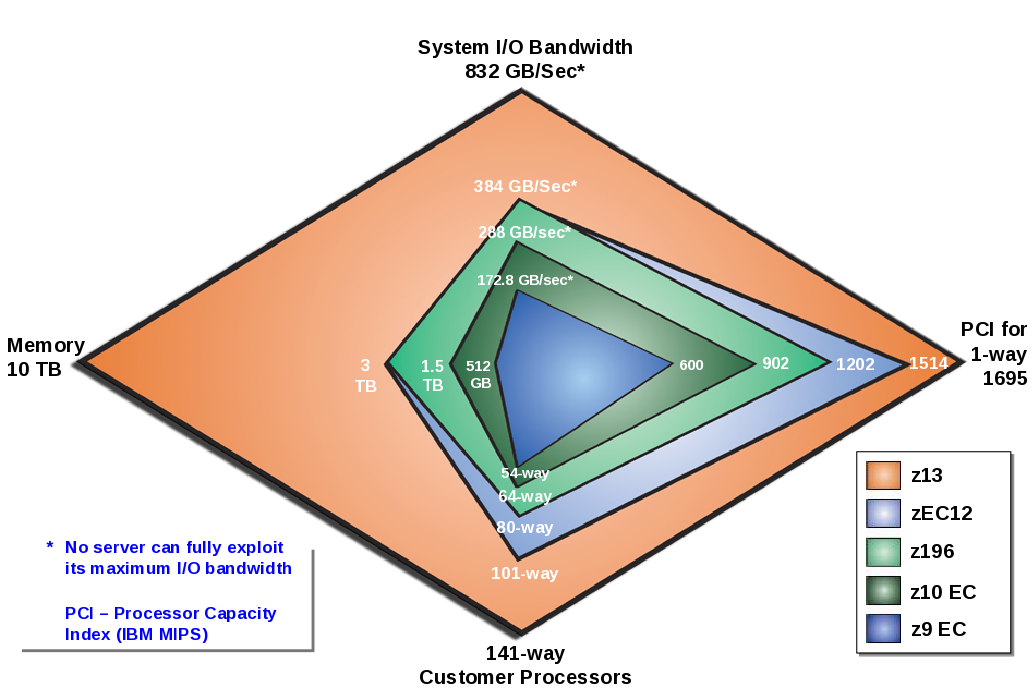

Changeable Things Need Graphing By Time Of Day

That is, of course, stating the obvious. But here is my graph that shows how some key metrics vary by time of day:

So, for example, Maximum Capacity Factor – being estimated from live measurements – varies by time of day and workload mix. Obviously, Capacity Factor – representing current load – also varies.

Notice how Average Thread Density – the average number of active threads when any are active – peaks during the day. This is a java-heavy workload, peaking in its use of zIIP during the day.

I’m not yet certain I’m wringing all of the insight out of the dynamics yet but I think this graph a good first step in that direction; My experience of this sort of thing is this graph will evolve a little – as I gain more experience.

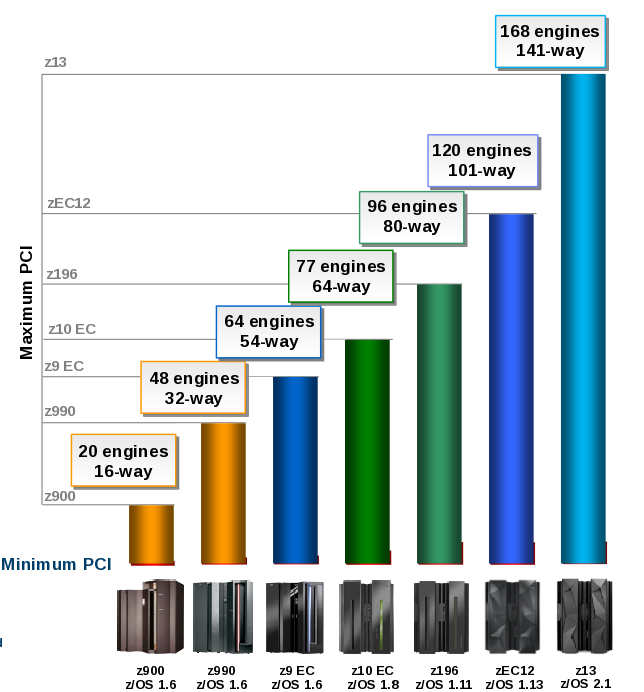

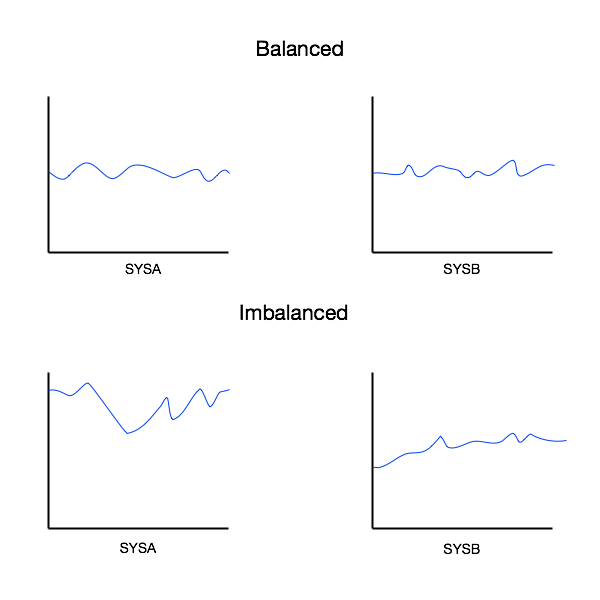

Engine-Level Analysis Is Interesting

I’ve been meaning to create this sort of graph for a long time – and SMT provides the perfect excuse.

The x axis is processor (or thread) sequenced by Core ID.3

You’ll notice the general-purpose (CP) processors come before the zIIPs (IIP).

Generating a readable graph but without too many x axis label suppressions is tough. But note for the zIIPS each core has two CPUs (with SMT–2) whereas the CPs have one.

While – from the previous graph – the picture is dynamic I think there is value in this shift-level graph. Doing a 3-dimensional one wouldn’t be hard but I think it would be hard to consume. (Time would be the third dimension.)

In any case there’s some interesting stuff in this graph:

The Parked processors (in turquoise) are interesting: No GCPs are permanently parked but several are partially parked. For the zIIPs, however, it’s a different story: 6 permanently are – 3 cores. 4

Certain things come in pairs: LPAR Busy and Core Productivity – as they are at the core level, rather than the thread level.

That’s not entirely true: GCPs don’t exhibit the “paired” behaviour. But that makes sense: Only a single thread is enabled on a core.

For GCPs CPU Ids are even numbers; For zIIPs they’re both odd and even. The zIIP values didn’t surprise me. The GCP ones did – and I’ve seen this for two customers’ data sets now.

Some of the zIIP CPU Ids are up in the x’70’ onwards range. This surprised me and caused me to have to widen the CPU Id field to 5 characters. 5

Today a lot of the above looks like tourist information. My golden rule with tourist information is there’s high probability it’ll turn out to be diagnostic rather than just interesting – some day.

Conclusion

So, I’m quite pleased with the way these graphs turned out; They do illustrate some of the SMT behaviours.

Obviously experience will condition how this reporting evolves. Watch this (or some similar) space!

-

“That must be nice for you” y’all cry. 🙂 ↩

-

It might also help if I come calling and throw graphs at you. 🙂 ↩

-

I’ve chosen to print CPIDs as hex but coreids as decimal. ↩

-

I’ve wanted to plot Parked Processors for a long time now; SMT is just an excuse. ↩

-

CPU Id is two bytes and the SLR query returns it as a decimal number – which necessitates 5 decimal positions. ↩