(Originally posted 2015-11-27.)

Applying the maxim “the customer is always right” this week revealed a bug in my analysis code. It also gave me the opportunity to write about how RMF sees the interaction between IRD Weight Management and Hiperdispatch.[1]

But let me start with some brief, basic information about the technologies in question. If only this proves useful the blog post will still have been worthwhile.

IRD Weight Management Basics

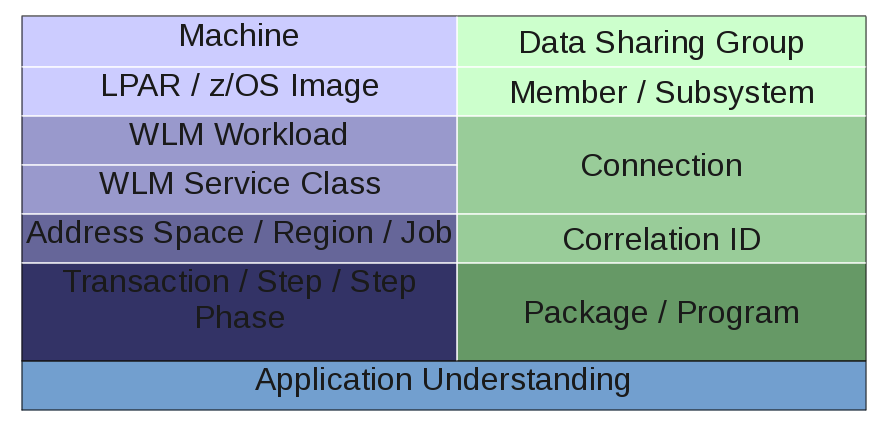

The initial implementation of PR/SM managed LPAR CPU access using static weights.

A long time later Intelligent Resource Director (IRD) introduced three new capabilities, two of which are related to CPU:

- Weight Management

- Logical Processor Management

The third, not the topic of this post, is about I/O priority management.

Weight Management introduced Dynamic Weights: Weights could shift between a group of LPARs on a machine, called an “LPAR Cluster”. The total weight for an LPAR Cluster is constant.

Weight shifting occurs in response to WLM’s view of goal attainment.

With Logical Processor Management an LPAR’s logical processors would be varied on and offline. (RMF Field SMF70ONT reflected for how long in an interval the logical processor was online.)

Hiperdispatch Basics

What follows is an extremely basic introduction to one aspect of Hiperdispatch. But it will, I think, suffice.

Without Hiperdispatch an LPAR’s weight is distributed evenly across all its online logical processors – so-called Horizontal CPU Management.

With Hiperdispatch, an LPAR’s weight is distributed unevenly (think “in a focused manner”) across its online logical processors – so-called Vertical CPU Management.

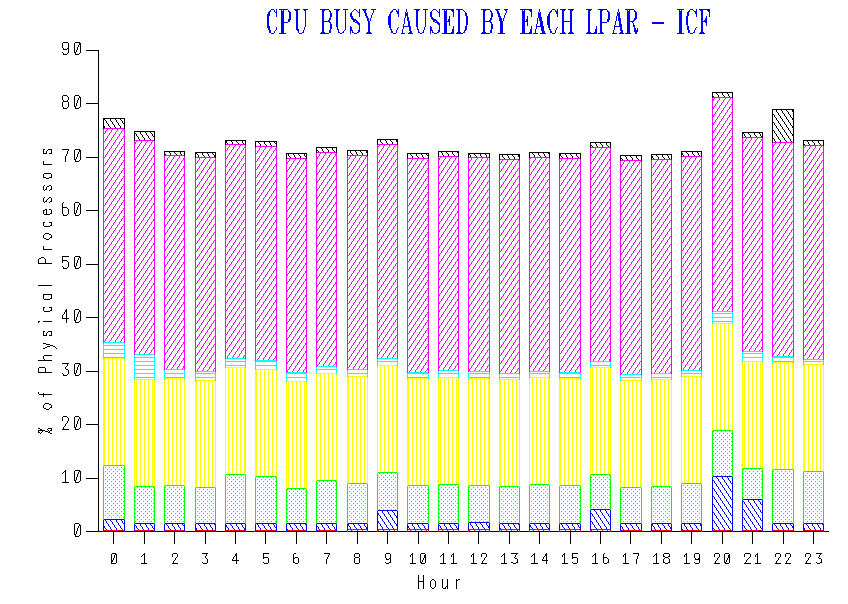

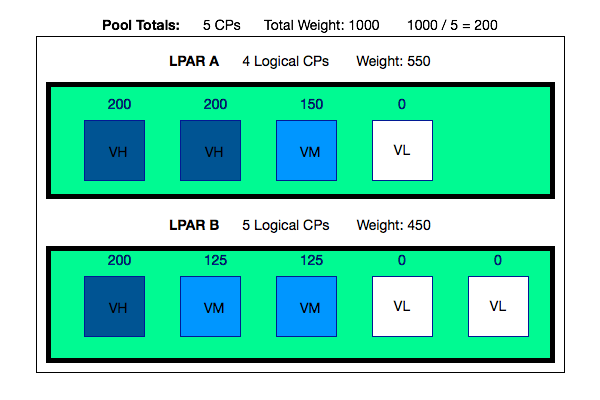

Consider the following (confected and so simpler than in real life) example of a machine’s processor pool. It contains 5 physical processors and the two LPARs’ weights add up to 1000.

So a physical processor’s weight’s worth is 1000 / 5 or 200. Hang on to the 200 as it’s important in what follows.

LPAR A has a total weight of 550 and 4 logical CPs. Rather than distribute the weight across all 4, a pair of CPs are designated Vertical High (VH) and assigned a weight of 200 each. The remaining 150 goes to a third CP, which is designated a Vertical Medium (VM). The fourth logical CP has a weight of 0 and is deemed a Vertical Low (VL). It can be “Parked”, meaning work is prevented from running there. It can also be “Unparked” and then work can run there.

LPAR B has a total weight of 450 and 5 logical CPs. It has 1 Vertical High, leaving a further 250 in weights to distribute. But rather than having 2 Vertical Highs and a Vertical Medium with (a rather puny) weight of 50 Hiperdispatch splits this remaining 250 across 2 Vertical Mediums, each with a weight of 125. The remaining logical CPs are, of course, 2 Vertical Lows with weights of 0.

It’s beyond the scope of this post to describe how logical processors map onto physical processors, except to say the Vertical Highs are pseudo-dedicated.

One thing to note is with Hiperdispatch enabled Logical CPU Management is no longer available. Hiperdispatch’s Parking and Unparking mechanism does a rather more sophisticated version of what Logical CPU Management did.

But the above example is a static picture.

Hiperdispatch Interaction With IRD Weight Management

With IRD Weight Management it’s possible [2] for the LPAR weights to shift. Taking the previous example and further supposing the two LPARs are in an LPAR Cluster…

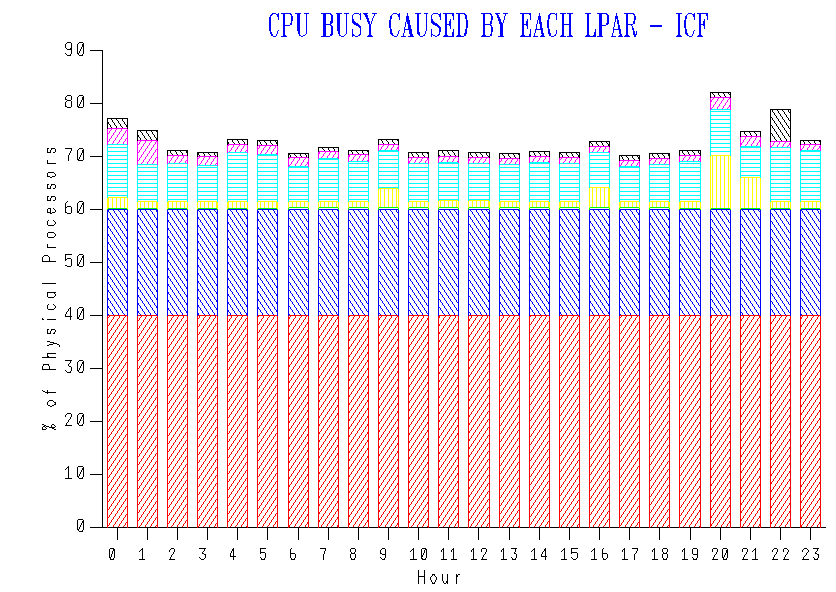

Suppose the weights shift by 50 in favour of LPAR A. So LPAR A’s new weight is 600 and LPAR B’s is now 400.

The picture is now as follows:

You’ll notice the Vertical Polarization is now different:

- LPAR A now has 3 Vertical Highs, rather than 2 Vertical Highs and 1 Vertical Medium. It still has 1 Vertical Low.

- LPAR B now has 2 Vertical Highs, rather than 1 Vertical High and 2 Vertical Mediums. The number of Vertical Lows is increased from 2 to 3.

Notice the number of logical processors assigned to each LPAR hasn’t changed, only the share of the processor pool (or the weights).

My Bug

My code said a specific LPAR had 7 General Purpose engines (GCPs) but the customer said it had 8.[3] And those were genuinely the numbers.

The customer, as I hinted, was right.

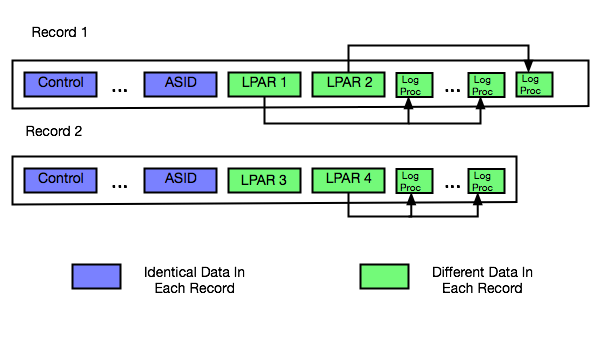

So let me explain now how RMF instruments all this (well a little of it ). SMF70POF is a field in the Logical Processor Data Section, of which there is one per logical processor for every LPAR (as described in Offline Processors Can’t Hurt You).

Here is an extract from the SMF manual:

- Bits 0 and 1 indicated whether and how the processor is polarized .

- Bit 2 indicates this changed during the interval.

Combinations of these bits do the job of telling me the story of the logical processor’s polarization through the RMF interval.

In a nutshell what happened was my code didn’t count processors that transitioned in the period of interest from e.g. Vertical High to e.g. Vertical Medium. It certainly counted processors in 6 categories:

- Unpolarized (or rather Horizontally Polarized )

- Vertical High

- Vertical Medium

- Vertical Low

- Vertical Transitioned

- Unknown

The code was meant to add up all totals but 1 was missing. And IRD shifting weights caused, for once, a processor to appear in the Vertical Transitioned category.

Anyhow the bug is fixed now and one of the results is this post. So I guess that’s progress. 🙂 And I’m genuinely grateful to the customer for spotting the error, even if it cost an hour or so of heartache.

-

I talk quite a bit in the current ITSO 1-day workshop on Performance and Availability. (These are not my slides .) ↩

-

In practice, in many customer sets of data the weights don’t shift, but for a substantial minority they do. Not dramatically, but they change. ↩

-

A bit like The Clash’s Wrong ’Em Boyo (from the excellent London Calling): “Stagger Lee throwed seven / Billy said that he throwed eight” – hence part of the title of this post. A gratuitous reference if ever there was one. 🙂 /> ↩

(Originally posted 2015-11-27.)

Applying the maxim “the customer is always right” this week revealed a bug in my analysis code. It also gave me the opportunity to write about how RMF sees the interaction between IRD Weight Management and Hiperdispatch.[1]

But let me start with some brief, basic information about the technologies in question. If only this proves useful the blog post will still have been worthwhile.

IRD Weight Management Basics

The initial implementation of PR/SM managed LPAR CPU access using static weights.

A long time later Intelligent Resource Director (IRD) introduced three new capabilities, two of which are related to CPU:

- Weight Management

- Logical Processor Management

The third, not the topic of this post, is about I/O priority management.

Weight Management introduced Dynamic Weights: Weights could shift between a group of LPARs on a machine, called an “LPAR Cluster”. The total weight for an LPAR Cluster is constant.

Weight shifting occurs in response to WLM’s view of goal attainment.

With Logical Processor Management an LPAR’s logical processors would be varied on and offline. (RMF Field SMF70ONT reflected for how long in an interval the logical processor was online.)

Hiperdispatch Basics

What follows is an extremely basic introduction to one aspect of Hiperdispatch. But it will, I think, suffice.

Without Hiperdispatch an LPAR’s weight is distributed evenly across all its online logical processors – so-called Horizontal CPU Management.

With Hiperdispatch, an LPAR’s weight is distributed unevenly (think “in a focused manner”) across its online logical processors – so-called Vertical CPU Management.

Consider the following (confected and so simpler than in real life) example of a machine’s processor pool. It contains 5 physical processors and the two LPARs’ weights add up to 1000.

So a physical processor’s weight’s worth is 1000 / 5 or 200. Hang on to the 200 as it’s important in what follows.

LPAR A has a total weight of 550 and 4 logical CPs. Rather than distribute the weight across all 4, a pair of CPs are designated Vertical High (VH) and assigned a weight of 200 each. The remaining 150 goes to a third CP, which is designated a Vertical Medium (VM). The fourth logical CP has a weight of 0 and is deemed a Vertical Low (VL). It can be “Parked”, meaning work is prevented from running there. It can also be “Unparked” and then work can run there.

LPAR B has a total weight of 450 and 5 logical CPs. It has 1 Vertical High, leaving a further 250 in weights to distribute. But rather than having 2 Vertical Highs and a Vertical Medium with (a rather puny) weight of 50 Hiperdispatch splits this remaining 250 across 2 Vertical Mediums, each with a weight of 125. The remaining logical CPs are, of course, 2 Vertical Lows with weights of 0.

It’s beyond the scope of this post to describe how logical processors map onto physical processors, except to say the Vertical Highs are pseudo-dedicated.

One thing to note is with Hiperdispatch enabled Logical CPU Management is no longer available. Hiperdispatch’s Parking and Unparking mechanism does a rather more sophisticated version of what Logical CPU Management did.

But the above example is a static picture.

Hiperdispatch Interaction With IRD Weight Management

With IRD Weight Management it’s possible [2] for the LPAR weights to shift. Taking the previous example and further supposing the two LPARs are in an LPAR Cluster…

Suppose the weights shift by 50 in favour of LPAR A. So LPAR A’s new weight is 600 and LPAR B’s is now 400.

The picture is now as follows:

You’ll notice the Vertical Polarization is now different:

- LPAR A now has 3 Vertical Highs, rather than 2 Vertical Highs and 1 Vertical Medium. It still has 1 Vertical Low.

- LPAR B now has 2 Vertical Highs, rather than 1 Vertical High and 2 Vertical Mediums. The number of Vertical Lows is increased from 2 to 3.

Notice the number of logical processors assigned to each LPAR hasn’t changed, only the share of the processor pool (or the weights).

My Bug

My code said a specific LPAR had 7 General Purpose engines (GCPs) but the customer said it had 8.[3] And those were genuinely the numbers.

The customer, as I hinted, was right.

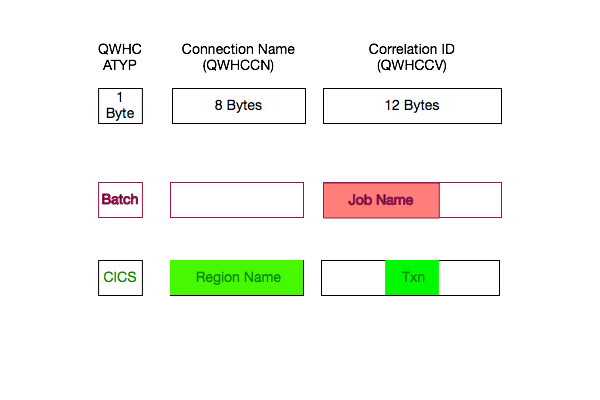

So let me explain now how RMF instruments all this (well a little of it ). SMF70POF is a field in the Logical Processor Data Section, of which there is one per logical processor for every LPAR (as described in Offline Processors Can’t Hurt You).

Here is an extract from the SMF manual:

- Bits 0 and 1 indicated whether and how the processor is polarized .

- Bit 2 indicates this changed during the interval.

Combinations of these bits do the job of telling me the story of the logical processor’s polarization through the RMF interval.

In a nutshell what happened was my code didn’t count processors that transitioned in the period of interest from e.g. Vertical High to e.g. Vertical Medium. It certainly counted processors in 6 categories:

- Unpolarized (or rather Horizontally Polarized )

- Vertical High

- Vertical Medium

- Vertical Low

- Vertical Transitioned

- Unknown

The code was meant to add up all totals but 1 was missing. And IRD shifting weights caused, for once, a processor to appear in the Vertical Transitioned category.

Anyhow the bug is fixed now and one of the results is this post. So I guess that’s progress. 🙂 And I’m genuinely grateful to the customer for spotting the error, even if it cost an hour or so of heartache.

-

I talk quite a bit in the current ITSO 1-day workshop on Performance and Availability. (These are not my slides .) ↩

-

In practice, in many customer sets of data the weights don’t shift, but for a substantial minority they do. Not dramatically, but they change. ↩

-

A bit like The Clash’s Wrong ’Em Boyo (from the excellent London Calling): “Stagger Lee throwed seven / Billy said that he throwed eight” – hence part of the title of this post. A gratuitous reference if ever there was one. 🙂 ↩